‘Cluster’ in-depth case studies and peer reviews: to move beyond the figures that are available for comparison, more qualitative studies can be carried out on activity domains where a region shows relative specialisation. This involves expert work on value chain analysis (undertaken in an international environment and enlightening the spatial division of labour), context conditions for the operation of the cluster, labour market situation, etc. It also involves an analysis of the linkages between the cluster and other clusters or industries, in order to examine whether one can talk about related variety across the areas of regional specialisation. One interesting approach is the ‘revealed skill relatedness’ (RSR) method (Neffke and Svensson Henning, 200922). RSR measures the degree to which industries share similar skill requirements, and this is seen as a very important vehicle for knowledge transfer between clusters (through people mobility). It is based on a network analysis using data on job changes between industries, showing proximity between industries in terms of skill sets.

Sophisticated analyses of clusters such as Henning et al. (2010)23 combine this type of analysis with a functional analysis linking economic structure to cluster challenges and assessing the functions taken by the cluster initiative. The functions analysed are: knowledge creation and knowledge diffusion; identification of opportunities and barriers; stimulation of entrepreneurship/management of risk and uncertainty; market formation; mobilisation of resources; and legitimation. These types of analysis are conducted by experts who study the cases in close cooperation with cluster actors: this helps to take into account innovation opportunities identified by leading actors (companies, universities, intermediaries, etc.) Mixing regional experts with international experts helps to give more weight to the international competitiveness issue. Adding key stakeholders from foreign clusters brings in a useful peer review dimension to the analysis.

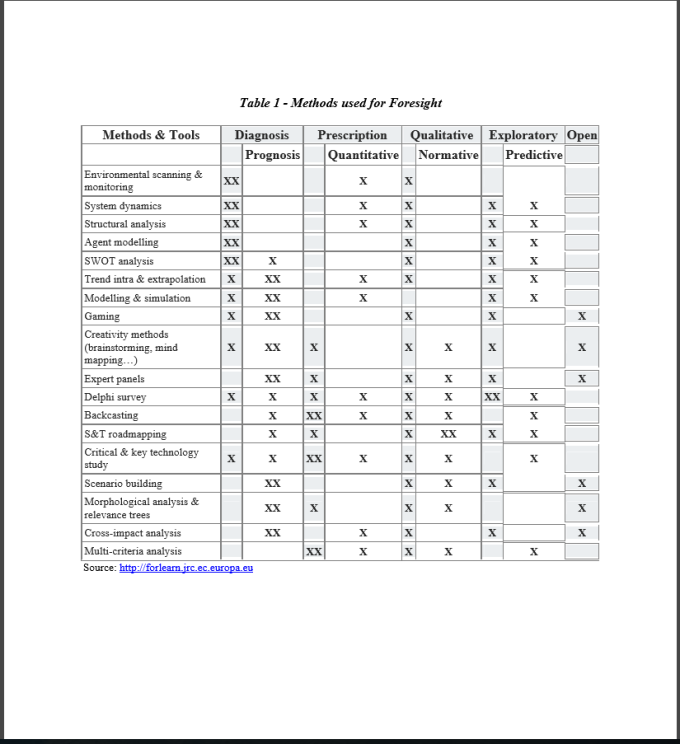

4. Foresight: the aim of foresight is to capture existing expert intelligence sources on future trends and make them accessible for present decision-making. The role of foresight is to elucidate possible paths for the future in order to open the debate on possible development paths. Foresight has the following characteristics24: Action-oriented; Open to alternative futures; Participatory; and Multidisciplinary. There is a multiplicity of methods that can be used and combined to implement foresight studies, the best known being expert panels and multi-round Delphi surveys. They differ in their expected benefits, conditions of use, time requirement, etc. and their common feature is that they rely heavily on expert knowledge and involve interactions between experts (Table 1; see more details on the FOREN website). For RIS3, foresight studies would ideally combine regional expertise with international expertise able to put regional assets in perspective with wider trends.

Step 2 – Governance: ensuring participation and ownership

At the beginning of a RIS3 design process, it is necessary to define the scope and expected goal, with a view to ensuring participation of the key actors and securing ownership of the approaches defined in the strategy.

With respect to the ultimate and long-term goal of the RIS3, the Vision for the future of the region should underpin the whole process: all analyses, debates, participative actions, pilot projects, etc. should be seen as participating towards the long term goal identified in the Vision. Potential actors relevant to the RIS3 process span from public authorities to universities and other knowledge-based institutions, investors and enterprises, civil society actors, and external experts who can contribute to the benchmarking and peer review processes.

Defining the scope of the RIS3 is crucial, since different stakeholders will have different expectations and agendas on the question at stake, often restricted to their own areas of action. Since RIS3 aims to achieve more effectiveness in all public action targeting regional transformation, a wide view of innovation is to be adopted. This will emphasise that innovation may occur everywhere, in different forms, and not only in the form of high technology development in metropolitan areas:

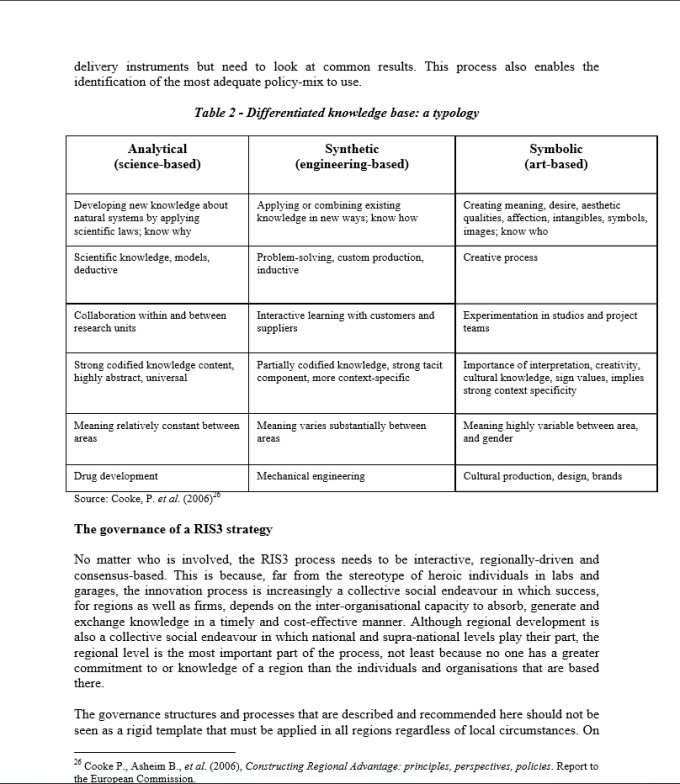

• Including innovation in services and in the public sector, in addition to innovation in the manufacturing sector which most policies currently target; • Encompassing innovation based on different types of knowledge bases, leading to different modes of innovation (Table 2): 1) the ‘STI’ (Science, Technology, Innovation) mode, based on analytical knowledge/basic research (science push/supply-driven approach) and synthetic knowledge/applied research (user-driven approach), emphasising product and process innovations; and 2) the ‘DUI’ (Doing, Using, Interacting) mode, based on synthetic and symbolic knowledge (market/user-driven), emphasising competence building and organisational innovations.25

With respect to policy areas and organisations involved, the above wide view means that several policy areas are concerned with the RIS3, beyond the traditional science and technology and economy ministries and agencies. Interministerial Committees are tools to cope with this need for a wide conclusion of stakeholders.

A RIS3 is an exercise that deals with policies developed by local, regional and national authorities (as well as EU Cohesion policy and EU research policy). This multi-level dimension of policy implies that governance mechanisms need to include stakeholders and decision-makers from these various levels. It also involves that links must be established between strategies for research (usually decided upon at national level) and strategies for innovation (usually under the responsibility of or developed in coordination with regional authorities). They use different

25 Lorenz P. and Lundvall B.A. (2006), How Europe’s Economies Learn. Coordinating Competing Models

A criticism that was sometimes levelled at the RIS process was that it was prone to being ‘captured’ by traditional interest groups in the region, groups that were more interested in preserving the regional status quo than transforming the regional economy through innovation. Although this criticism can be overdone (because regional governments, for example, had to be involved in the RIS process), the design of the RIS3 architecture needs to anticipate the risk of capture and make it more difficult for traditional groups to frustrate the process.

In the Open Innovation era, where social innovation and ecological innovation entail behavioural change at the individual and societal levels if the challenges of health, poverty and climate change are to be addressed, the regional governance system should be opened to new stakeholder groups coming from the civil society that can foster a culture of constructive challenge to regional status quo.

In particular, in order to guarantee a livelier and truly place-based entrepreneurial process of discovery that generates intensive experimentation and discoveries, it is imperative that new demand-side perspectives, embodied in innovation-user or interest groups of consumers, are represented along with intermediaries who offer a knowledge-based but market-facing perspective. This means that the traditional, joint-action management model of the triple helix, based on the interaction among the academic world, public authorities, and the business community, should be extended to include a fourth group of actors representing a range of innovation users, obtaining what is called a quadruple helix.27 This is the necessary organisational counterpart of an open and user-centred innovation policy, because it allows for a greater focus on understanding latent consumer needs, and more direct involvement of users in various stages of the innovation process. RIS3 processes can develop environments which both support and utilise user-centred innovation activities also with the aim of securing better conditions to commercialise R&D efforts.

The quadruple helix allows for a variety of innovations other than the ones strongly based on technology or science, in the spirit of the wide concept of innovation at the basis of RIS3, but it requires significant flexibility, adaptation of processes, acquisition of new skills, and potential re-distribution of power among organisations. This in turn calls for collective leadership and moderation of the process as necessary practices for achieving successful governance.

Leadership assumes many forms. Three different, but equally important forms of leadership are the following: political leadership (the people who are chosen by the electorate to represent us and to lead our governments); managerial leadership (the people who manage the ‘enterprise function’ in the public, private and third sectors); and intellectual leadership (the people who play a leading role in connecting their universities to the worlds in and beyond their regions). The Guide does not presume to suggest which form of leadership is the best or the most appropriate, because this is a decision that needs to be made at the regional level, where the choice can be informed by local knowledge of competence, credibility and character, the essential attributes of a leader.

27 Arnkil R., et al. (2010), Exploring Quadruple Helix. Outlining user-oriented innovation models. University of Tampere, Work Research Center, Working Paper No. 85 (Final Report on Quadruple Helix Research for the CLIQ project, INTERREG IVC Programme).

38

Although a leader needs to have certain personal attributes, like the ones identified above, leadership research has taken a ‘relational turn’ in recent years. Rather than being a static ‘thing’ that a minority of people possess, leadership is now understood as a dynamic relationship between leaders and led in which both sides play an active role in finding joint solutions to common problems. In this context, a way to secure understanding and ownership of the main strategic orientations is to allow for effective collaborative leadership among the key actors involved in the process. When innovation processes embrace many different areas of the society, as in the case of RIS3, collaboration among stakeholders holds the key to successful implementation of innovative practices, implying that leadership has to be shared and exercised across organisations. Collaborative leadership requires the emergence of collaborative practices, as actors must find ways of managing conflict themselves.

In order to moderate the RIS3 design process, actors playing the role of boundary spanners between the organisations are needed. These are actors endowed with an interdisciplinary knowledge or experience of interaction with several different types of organisations; hence they can facilitate new connections across sectors, foster new conversations between disciplines, and inject novelty into the process. This in turn helps to overcome the sectoral and disciplinary silos that reproduce old habits and routines, locking regional economies into their traditional paths of development.

Boundary spanning skills tend to emerge from activities that straddle sectors, disciplines and professions and they are invariably fashioned in action learning environments where there is a high degree of novelty associated with the activity. Examples of such activities include technology transfer, knowledge exchange, venture funding, regional economic development, business services, and management consultancy, all of which afford an overview of the regional economy. Formal recognition of the boundary spanning role, and its significance for universities, businesses and the regional economy, would do much to promote a skill set that is critically important to the moderation of the RIS3 process, particularly of the entrepreneurial process of discovery, which lies at the heart of the process.

As far as the structure of the management body is concerned, it will clearly vary according to local circumstances, it must be supported by robust governance arrangements. The RIS experience is instructive here because it shows that local diversity can exist within a generic governance system. The governance system of a typical RIS project revolved around three elements — Steering Group, Management Team and Working Groups — and they worked in the following way:

• Steering Group: the SG was responsible for the overall performance of the project and it normally included members of the business community, local and regional government, and key innovation actors, all of whom were expected to embed the project in their respective fields of activity. The size of the SG was always carefully considered: too few members could compromise the consensus-building process, while too many members could be a recipe for a bureaucratic and unwieldy process. An appropriate balance was a membership of around fifteen people meeting as a group every two or three months. The main tasks would typically include the following: setting objectives and monitoring activities, selecting the members of the Management Team, supervising the work

39

programme, political and institutional support, and liaising with the European Commission. The chair of the SG was invariably a local notable drawn from the business community, academia or the public sector; • Management Team: the MT was responsible for implementing the RIS project under the general guidance of the SG. The composition of the MT varied a lot between the regions, though all regions had a Project Manager who was supported by a small team of up to three people. The main tasks of the MT often included the following: liaising with the EC and providing progress reports, providing a secretariat to the SG, launching and coordinating the study assessment tasks of the project, and fostering regional consensus around the project, acting as a focal point for networking with other RIS regions to draw on their experiences. Choosing the location of the MT was an important decision because how the project was perceived was largely a function of where it was physically situated; • Working Groups: the WG mechanism fulfilled two purposes: it helped to build regional consensus for the RIS project throughout the region and it provided a means to engage the business community, especially if the Working Groups were sector-based, as they were in regions with strong sectoral specialisations. Where they were most effective, Working Groups had clearly defined terms of reference and a credible timetable for the delivery of results. The conclusions of the Working Groups were supposed to inform the strategic discussions in the Steering Group.

Many regions will be able to draw on their unique RIS experience when they embark upon their RIS3 strategies because these two processes have a good deal in common. It is important to remember that regions are not being asked to do something totally new when they begin the RIS3 journey of discovery. The original RIS experience also offers some instructive lessons with regard to the involvement of the business community in the process:

• Communications: a clear communications strategy was deemed to be of enormous importance, especially for the business community. The businesses actually involved in RIS projects also required honest and timely feedback; • Management: the Management Team and Steering Group personnel often played a key role in maintaining effective communication, especially where the chair of the Steering Group or the leader of the Management Group was a prominent local business leader or a wellconnected local networker (as they were in Yorkshire and Humber and Dytiki Macedonia respectively); • Sector Champions: Sector champions can help to engage the local business community in traditional sectors as well as in new or emerging sectors, both of which need to embrace innovation; • Local Media: the involvement of local media helped to raise the profile of the RIS exercise, especially in RIS Aragon, where two journalists from daily newspapers were involved in the RIS process from the outset. Frequent coverage in the media helped the project to resonate in the local business community; • Pilot Projects: To overcome the criticism of the RIS process being no more than a ‘talking shop’, it was found that pilot projects led by local business leaders were an effective form of action learning which generated useful information as well as helped to maintain the active engagement of the business community.

40

Some or all of these engagement mechanisms will be relevant to the RIS3 exercise because the latter involves an even deeper and more iterative relationship with the business community. But innovation is increasingly a collective social endeavour, and the business community should not be expected to carry the full burden of innovation on its own shoulders. Success in the innovation stakes will increasingly go to countries and regions that transcend the sterile ideological debate about private versus public and embrace the fact that innovation is a collective social endeavour, at the heart of which is a judicious private + public partnership.

Getting firms, universities, development agencies and regional governments to accept that innovation is a collective social endeavour — where participants freely acknowledge that working in concert can deliver far more than working in isolation — is arguably the most important ingredient in the ‘recipe’ for purposeful entrepreneurial search. This does not displace the firm from the forefront of the search process; but it does mean that the costs and risks associated with entrepreneurial search are shared and therefore do not become too prohibitive for the firm that is leading the search process.

To tap the potential of related variety, regional authorities and development agencies will need to behave less like traditional public bureaucracies and more like innovation animateurs, brokering new connections and conversations in the regional economy. New opportunities are emerging in old regions as a result of connections and conversations that are now occurring but which never occurred in the past despite the parties being co-located in the same region (proving that cognitive proximity is far more important than mere physical proximity).

The onus of responsibility for creating such iterative processes rests primarily with public sector bodies, especially universities, development agencies and regional governments. Learning by doing will help these public sector bodies to appreciate the needs of firms, but more formal action learning programmes will also be needed. A good example of such a programme is the Place-Based Leadership Development Programme, which regions may wish to adapt and adopt to help them acquire the iterative skills needed in the RIS3 exercise (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – A Place-based leadership development programme

Under such a programme, universities, development agencies and regional governments could jointly identify a project to explore the prospects for related variety in the regional economy. Collaborative leadership development expertise would be developed through each actor bringing substantive knowledge (‘know what’), professional networks (‘know who’) and skills (‘know how’) to the initiative and explicitly sharing their knowledge and experience with other members of the project team. The participants are then encouraged to introduce these collaborative leadership skills back into their respective public bodies to help the latter to behave less like traditional bureaucracies and more like animateurs of innovation and development. The formation of a Knowledge Leadership Group would give an institutional expression to the alliance between universities, development agencies and regional governments.

Finally, as the original RIS programme took consensus-building seriously, it is worth distilling the lessons from that experience as a starting point for the RIS3 exercise. In the best cases, the consensus-building process focused on three inter-related themes, namely awareness-raising, priority-shaping and fostering a sense of ownership, each of which merits attention. Awarenessraising was achieved in a number of different ways, including: (i) a project launch event such as a high profile seminar or conference (ii) a series of presentations throughout the region to key sectors, especially to the business community and the higher and vocational training institutions (iii) publicity through radio, television and newspaper coverage (iv) the distribution of customised brochures (v) the creation of a specialised project web site and (vi) the use of iconic companies in the region as ambassadors for the project. Awareness-raising needs to be measured and also needs to be calibrated with action, otherwise there is a danger that expectations will be raised too early in the process, leading to disillusionment before the project has had time to show some tangible results.

Enabling key actors to shape the priorities of the programme proved to be an important way of retaining their commitment. Each actor will have a keen sense of their own priorities, as well as their own diagnosis of the strengths and weaknesses of the regional economy, and these views were subjected to critical review through a combination of SWOT analyses and collective debate. Giving all participants the opportunity to shape the policy priorities is the key point to establish because this process of open deliberation spawned a sense of ownership.

A sense of ownership was a natural outcome of the consensus-building process when the latter was properly conducted. A sense of shared ownership among the Steering Group members proved to be particularly important and this intangible asset was enhanced by regular consultation with participants and by securing concrete outputs, proving that the RIS exercise was about results as well as processes, more than just a ‘talking shop’ in other words.

Multi-level/multi-fund approach to RIS3

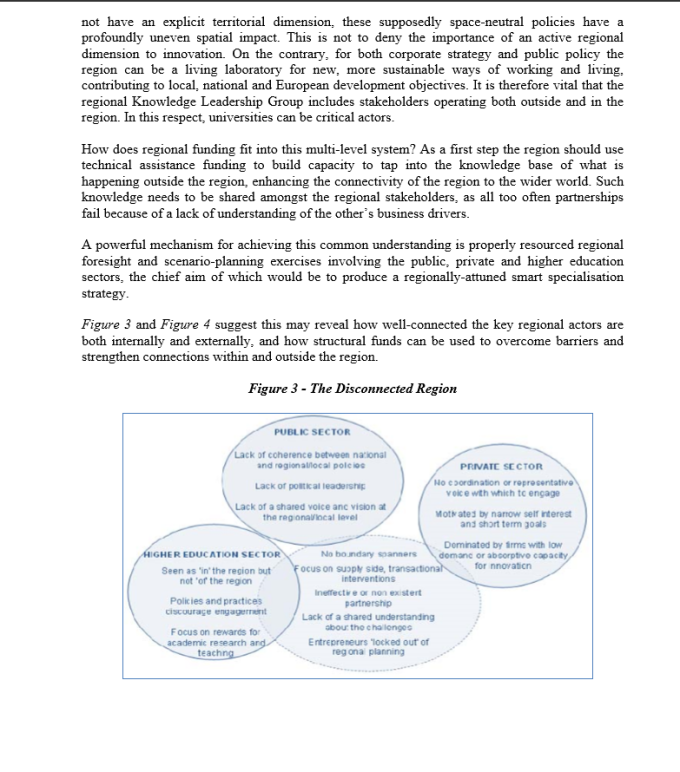

The process of innovation and the policies that shape it operate at multiple levels, from the global to the local. For many key actors involved in the region, notably private firms and leading universities, the development of the region will not be their primary focus. While regional public authorities do have a territorial responsibility, innovative public services are increasingly being delivered by external organisations. At the same time, although many national government agencies and the European Union itself operate a range of innovation-orientated policies that do

41

Under such a programme, universities, development agencies and regional governments

Step 3 – Elaboration of an overall vision for the future of the region

This step is the development of a shared and compelling Vision on the economic development potential of the region and the main direction for its international positioning. It is a highly political step. Its value mainly rests on getting the political endorsement for the subsequent steps, particularly for the implementation of the strategy.

The main quality of a Vision is its mobilising power: it should attract regional stakeholders around a common bold project, a dream, which many feel they can contribute to and benefit from. It will be easier to run this step when a regional ‘grand figure’ (a politician, an industrialist, a leading academic, a well-known artist…) pushes the Vision forward on a large scale. Times of crisis often provide a good opportunity to generate such new Visions, starting from the wellacknowledged need to escape the crisis. The main difficulty for a Vision is to be ambitious but still credible: few regions can realistically claim that they want to become the ‘most innovative region of the EU’. Over-ambitious claims might undermine a RIS3 from the start, if the Vision cannot be taken seriously by regional stakeholders.

At this stage, the purpose is to reach the willingness to act towards the transformation of the regions and support the regional consensus necessary to perform the other steps.

The ‘dream’ should be bold and wide enough to accommodate realistic priorities and specific development paths. The Vision should pinpoint possible paths for the economic renewal and transformation of the region. It may, for example, present the region as a new technology hub, based on the high density of technology-driven public and private actors; it may stress its potential as the central node in a cross-border area and emphasise its connectivity assets; it may make the link between exceptional natural assets and innovation potential; it may build on the skill sets of the population as the main driving force for future development, it may use flagship projects in cultural and creative industries to develop the innovative image of the region, etc.

Finally, the Vision should also include justifications for its relevance in terms of meeting societal challenges, such as providing more healthy living conditions for its citizens, reducing outmigration, providing new employment opportunities for specific categories of the population, combating social divide, etc. These justifications go much beyond the alleged classical benefits of innovation for job and economic value creation.

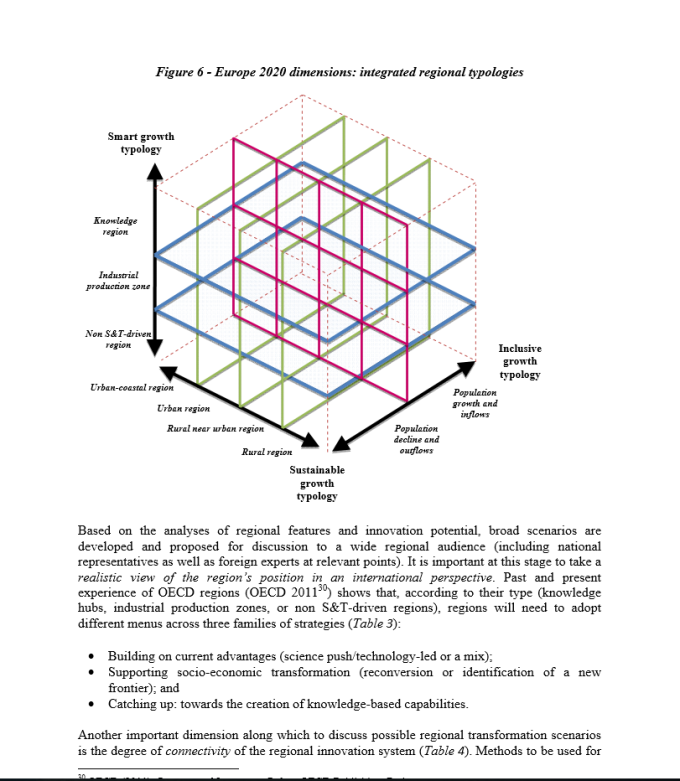

The elaboration of the overall vision for the future requires the identification of the combined place-specific features of a region. In order to help policy-makers and managing authorities to identify the dominant characteristics of their own administrative regions, it is possible to construct a three-dimensional box diagram, within which individual administrative regions can be positioned or situated (see Figure 6). The sides of the box reflect the three priorities of Europe 2020, and each side of the box provides the typology which most concisely captures the major features associated with each of the individual Europe 2020 challenges.28 28 The regional categories depicted by the sides of the box diagram here with regard to the smart growth, sustainable growth and inclusive growth dimension of Europe 2020, are exactly the same categories as those used in the

46

For the purposes of this guide, the classification scheme used here is intended to be indicative rather than definitive and schematic rather than exhaustive, and in particular cases other classification schemes may be more appropriate.

For the Europe 2020 smart growth typology, the most concise framework is provided by the OECD (2011) regional innovation typology in which regions are grouped into three broad types, namely knowledge regions, industrial production zones, and non-Science & Technology-driven regions, within which there are various sub-categories. These three broad categories reflect the major observed differences in terms of the relationships between knowledge, innovation and regional characteristics. EU regions can be classified into one of these broad smart growth groupings in terms of the role played by knowledge in fostering their local innovation processes.

For the Europe 2020 sustainable growth typology, the classification scheme which most concisely captures the different combinations of environmental and energy challenges is based on the relationship between the built environment and the natural environment. At its most fundamental level, this gives us four types of region, namely regions which in nature are primarily rural regions, rural near urban regions, urban regions, and urban-coastal regions.29

For the Europe 2020 inclusive growth typology, the classification scheme which most concisely captures the very different social inclusion issues faced by regions is that which is also adopted by the ESPON (2010) DEMIFER project. This has two broad types of region, namely regions facing population decline and population outflows and regions facing population growth and population inflows. Migration is a highly selective phenomenon and mobility is highly correlated with skills and income. Population outflow regions generally face a combination of more rapid population ageing and economic decline, which in turn have significant adverse impacts on both innovation and environmental issues.

In Figure 6, each individual axis represents one of the three Europe 2020 agenda dimensions. The combination of the smart growth, sustainable growth and inclusive growth typologies allows for twenty-four possible tripartite types of place characteristics, each of which is depicted by a different cell in the three-dimensional box of regions.

results/outcome indicators classification scheme on the use of results/outcome indicators within a reformed Cohesion Policy adopted by the international panel of experts advising the EU Commissioner for Regional Policy Johannes Hahn, Directorate General for Regional Policy. 29 This sustainable growth classification scheme of primarily urban, primarily rural near urban, primarily rural and primarily urban and coastal, closely resembles the OECD (2011b) regional typology based on the dominant built environment and natural environment features, which uses three types of regions, namely predominantly urban regions, predominantly intermediate regions, and predominantly rural regions, respectively.

Table 4 – Innovation strategies for different types of regions according to internal and external connectivity

Connecting globally Sustaining momentum

Cluster building Deepening pipelines

Types of regions Peripheral regions lacking strong research strengths and international connections

Regions with strong local cluster organisations wellnetworked with policy actors

Small groupings of competitive businesses with limited local connectivity

Regions dependent on limited number of global production networks/ value chains

Key challenge Building a global pipeline

Building up new regional hinges connected to regional firms — building critical mass

Improving local networking connecting more local actors to growing regional network

Extending connectivity and networks around hub

Main policy option

Helping regional actors take first steps in international cooperation

Bringing outside actors in, and helping to collectively shape future trends

Channelling innovation support to stimulate growth through regional clusters

Helping second-tier innovators become market leading and shaping

Example of regions

Madeira, Tallinn, Tartu, Attica, Sardinia

Ile-de-France, Baden-Württemberg, Flanders, Toronto

Skane, Navarra, Auckland, NordPas-de-Calais

Piemonte, Eindhoven, Seattle, North East of England

Source: Regional Innovation Monitor,32 based on Benneworth and Dassen 201133

An element closely intertwined to formulating an effective vision is RIS3 communication. Good communication of the RIS3 is essential to ensure its endorsement by all stakeholders of the region, and beyond. Communication is needed all along the process, adapting the content to the stage reached (adoption of a vision, adoption of policy priorities, endorsement of an action plan, implementation of key projects, etc.. The implementation of RIS across Europe has delivered the following lessons regarding the crucial components of a communication strategy, which are also valid in the RIS3 context (Innovating Regions in Europe Network 2005)34:

1. Definition of goals: the main goal should be to place the RIS project in a national and European context, to inform and create an attractive image for the identified target group of the project. But it can also pursue the goal of identifying and extending this target group by embarking stakeholders that are not yet part of the process. And it may serve the wider purpose of informing public opinion about the need to support the development of knowledge-based business in the region;

32 http://www.rim-europa.eu. 33 Benneworth P. and Dassen A. (2011), Strengthening global-regional connectivity in regional innovation strategies. Report for the OECD. 34 Innovative Regions in Europe Network (2005), RIS Methodological Guide, Stage 0.

50

2. Identification of the stakeholder groups and their motivation: different target groups have different needs and should be reached with different tools. Traditional SMEs, high-tech companies, universities, transfer institutions, business intermediaries, local and regional authorities, national bodies, the media, etc. have a different understanding and expectations of an RIS. The goal of the strategy should be to make sure that they all endorse and contribute to the strategy from their perspective. To this end, appropriate communication methods and expected results need to be spelled out for each target group;

3. Definition of traditional communication tools: the tools include the use of a logo which builds and reinforces the regional identity and puts innovation at its core; attractive and dynamic web pages, including parts in English for wider dissemination; newsletters and leaflets to complete the information with traditional communication tools; specific publications on certain aspects of the RIS (key analyses, peer review reports, etc.); conferences and seminars, including participation in international conferences, which give the opportunity to diffuse synthetic material on the RIS; and press and TV campaigns. The content of the communication should include strategic lines and priorities but also communication and demonstration on flagship projects;

4. Definition of active communication tools: active tools mainly include pro-active activities such as targeted visits to stakeholders or concerted workshops and seminars. Examples of active tools are: visiting the sites, marketing of the participants to the project; press conferences (various with different scenarios); round table discussions; meetings with local and regional politicians; etc. Conferences and seminars are frequently used: launch conferences ease the awareness and stimulate the participation of the actors in the exercise, but it is not easy to decide on the content of the message to be passed on. Conferences in the middle of the process stimulate the participation of regional actors in the construction of the strategy and validation of analyses. An end conference is necessary since all stakeholders in the region are supposed to adhere to the strategy and implement it in their own area.

51

Step 4 – Identification of priorities

Smart specialisation involves making smart choices. In fact, smart specialisation is all about facilitating that choice, selecting the right priorities and channelling resources towards those investments that have the potentially highest impact on the regional economy. The priority setting for national and/or regional research and innovation strategies for smart specialisation should consist of the identification of a limited number of innovation- and knowledge-based development priorities in line with existing or potential sectors for smart specialisation, on the basis of the elements and steps presented in this guide.

Priorities in RIS3 need to:

• Define concrete and achievable objectives. These objectives should be based on present and future competitive advantage and potential for excellence, as derived from the analysis of regional potential for innovation-driven differentiation; • In addition to technological, sectoral or cross-sectoral priority areas, horizontal priorities need to be defined. These could involve the diffusion and/or application of Key Enabling Technologies (see Annex II), aspects related to social innovation, or the financing of the growth of newly established companies, which is often a bottleneck in many regions that have prioritised the creation of new technology-based firms but fail to see these firms grow and create jobs.

As has been explained in previous sections, the selection process needs to be based on quantitative as well as qualitative information on the different possible domains for a national/regional smart specialisation. The key criteria for filtering the range of possible priority areas down to only a few priorities are:

• the existence of key assets and capabilities (incl. specialised skills and labour pools) for each of the areas proposed and, if possible, an original combination of these (cross-sector; cross-cluster), • the diversification potential of these sectors, cross-sectors or domains, • critical mass and/or critical potential within each sector, • the international position of the region as a local node in global value chains.

All this relevant information is to be examined by decision/policy-makers in order to select a few priorities focusing on the existing strengths of the economy but also on emerging opportunities. A good smart specialisation strategy will catalyse structural change and the emergence of critical clusters so that agglomeration externalities, economies of scale, economies of scope and local spillovers can be fully realised in the process of knowledge production and distribution.

A regional economy clearly provides the appropriate dimensional framework for such processes of decision, strategic implementation, agglomeration of resources and materialisation of spillovers. However, national economies might also be a good framework, particularly in the case of small countries.

52

But how to present the prioritised areas? If the areas are presented in a too generic way, such as eco-innovation, green energy, sustainable mobility or healthcare, most regions will fail to point out their unique competitive strengths. To be credible, effective and suitable for a concrete action plan (see next step), the priorities need to be expressed more precisely, such as ICT-based innovation for active ageing, innovative solutions to reduce city congestion, wood-based solutions for eco-construction, etc.

Prioritisation always entails risks for those who have to select those few domains that, as a result, will get privileged access to public funding. Common approaches followed in the past, which should not be repeated, were:

• spreading the money across the most powerful lobbies with the frequent outcome that there were too many priorities aimed at preserving the status quo rather than looking at future opportunities; or • imitating other regions. In that case, if the choice proved to be a mistake, at least this was a mistake others have made as well. At the end of the day regions contributed to producing a system with too many small sites doing the same things and where agglomeration externalities were dissipated.

These approaches failed to take into account the essential knowledge in this matter, which is entrepreneurial knowledge. Research and innovation strategies for Smart Specialisation should address the difficult problem of prioritisation and resource allocation based on the involvement of all stakeholders in a process of entrepreneurial discovery, which should secure a regionally- and business-driven, inclusive and open prioritisation process.

There are different methodologies for organising such processes, e.g. surveys, seminars with participatory leadership methods, crowdsourcing, etc.

Such an open, participatory process, together with reliance on robust evidence based on regional assets, are the best guarantees to avoid both the risk of capture by interest groups and the risk of lock-in into traditional activities. Once the priorities are adopted it is important that the strategy is validated and endorsed by a broad regional constituency (in the form of a representative Council or Forum, or through top-level events).

53

Step 5 – Definition of coherent policy mix, roadmaps and action plan

Experience with Regional Innovation Strategies throughout Europe has shown that it is good practice to combine the adoption of strategies with an agreement on an Action Plan and even the simultaneous launch of pilot projects (IRE 2007).35 Analytical and Strategic phases tend to remain invisible to many field actors. Strategies that stop before this step run the risk of remaining unimplemented and/or not credible. Pilot projects, once their success is proven, can be used as flagships of the RIS3, to demonstrate that they go beyond rhetoric and involve concrete action.

As priority areas for the region’s transformation are defined in the previous step, a coherent multi-annual Action Plan should be elaborated by the RIS3 management bodies, including:

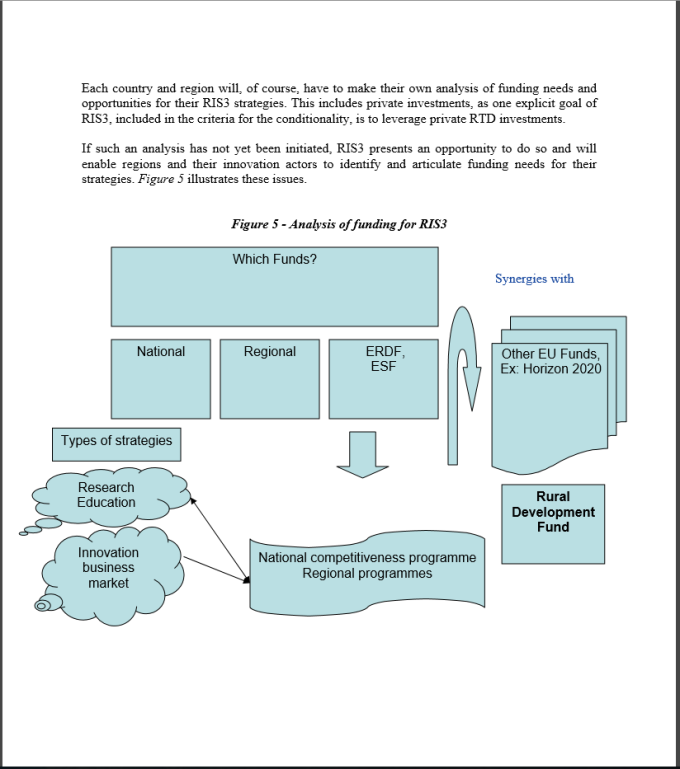

• Definition of the broad action lines corresponding to the prioritised areas and the challenges faced within these areas; • Definition of delivery mechanisms and projects; • Definition of the target groups; • Definition of the actors involved and their responsibilities; • Definition of measurable targets to assess both results and impacts of the actions; • Definition of timeframes; • Identification of the funding sources, targeted to the several groups and projects (developing and completing Figure 5).

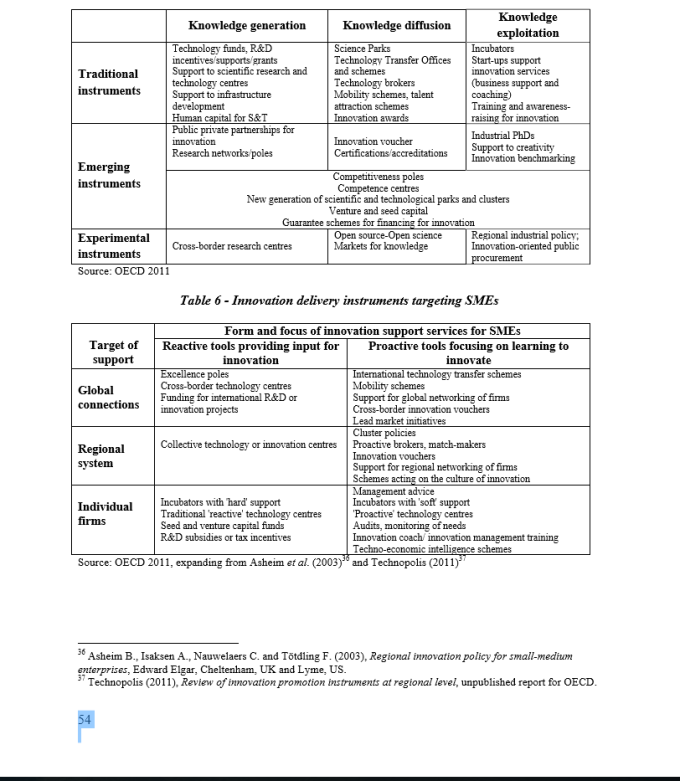

This planning process involves both the incorporation of existing programmes and instruments, on the basis of evidence on their effectiveness and relevance for the prioritised areas, and inclusion of new instruments, justified according to their contribution to the overall strategy goals. There is a wide menu to choose from in order to compose a balanced and appropriate policy mix. It is useful to use taxonomies, such as those presented in Table 5 and Table 6, to determine whether these instruments are likely to address, collectively, the strategic goals of the RIS3.

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 present examples of strategies and associated mixes of action lines and instruments, according to regional types and to the institutional power of the region: this latter element underlines the necessity to embed national-level policies into the policy mix, seen from a regional perspective. Each action line and instrument needs to be accompanied by measurable indicators reflecting results achieved, according to the mission and objective, but also impacts reached, assessed through evaluations.

35 Innovative Regions in Europe Network (2007), RIS Methodological Guide, Stage 2.

54

Table 5 – Regional innovation delivery instruments: a taxon

One thought on “‘Cluster’”