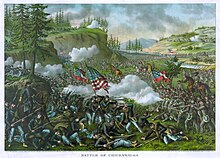

The United States dropped nuclear weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively, during the final stage of World War II. The United States had dropp…

Month: January 2017

The United States dropped nuclear weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively, during the final stage of World War II. The United States had dropped the bombs with the consent of the United Kingdom as outlined in the Quebec Agreement. The two bombings, which killed at least 129,000 people, remain the only use of nuclear weapons for warfare in history.

In the final year of the war, the Allies prepared for what was anticipated to be a very costly invasion of the Japanese mainland. This was preceded by a U.S. conventional and firebombing campaign that destroyed 67 Japanese cities. The war in Europe had concluded when Nazi Germany signed its instrument of surrender on May 8, 1945, just after Hitler committed suicide. The Japanese, facing the same fate, refused to accept the Allies’ demands for unconditional surrender and the Pacific War continued. The Allies called for the unconditional surrender of the Japanese armed forces in the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, 1945—the alternative being “prompt and utter destruction”. The Japanese response to this ultimatum was to ignore it.

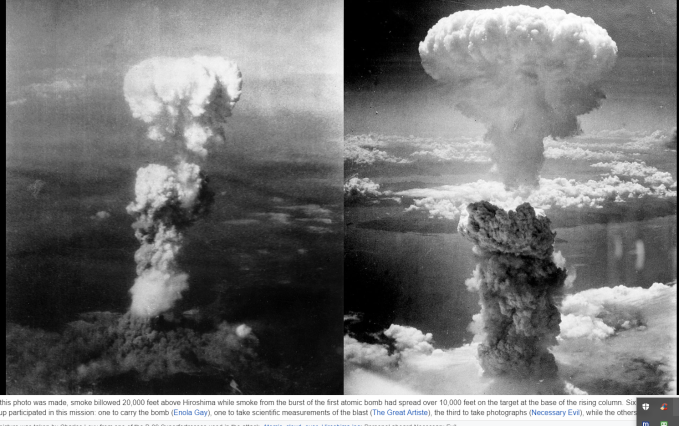

By August 1945, the Allies’ Manhattan Project had produced two types of atomic bombs, and the 509th Composite Group of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) was equipped with the specialized Silverplate version of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress that could deliver them from Tinian in the Mariana Islands. Orders for atomic bombs to be used on four Japanese cities were issued on July 25. On August 6, the U.S. dropped a uranium gun-type (Little Boy) bomb on Hiroshima, and American President Harry S. Truman called for Japan’s surrender, warning it to “expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.” Three days later, on August 9, a plutonium implosion-type (Fat Man) bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Within the first two to four months of the bombings, the acute effects of the atomic bombings killed 90,000–146,000 people in Hiroshima and 39,000–80,000 in Nagasaki; roughly half of the deaths in each city occurred on the first day. During the following months, large numbers died from the effect of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness and malnutrition. In both cities, most of the dead were civilians, although Hiroshima had a sizable military garrison.

Japan announced its surrender to the Allies on August 15, six days after the bombing of Nagasaki and the Soviet Union‘s declaration of war. On September 2, the Japanese government signed the instrument of surrender, effectively ending World War II. The ethical justification for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is still debated to this day, mainly because more than a hundred thousand civilians were killed.

- 1Background

- 2Preparations

- 3Hiroshima

- 4Events of August 7–9

- 5Nagasaki

- 6Plans for more atomic attacks on Japan

- 7Surrender of Japan and subsequent occupation

- 8Depiction, public response, and censorship

- 9Post-attack casualties

- 10Hibakusha

- 11Debate over bombings

- 12See also

- 13Notes

- 14References

- 15Further reading

- 16External links

Background

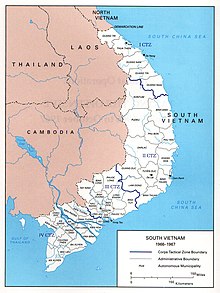

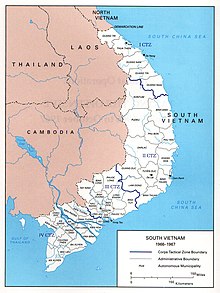

Pacific War

Situation of Pacific War by August 1, 1945. Japan still had control of all of Manchuria, Korea, Taiwan and Indochina, a large part of China, including most of the main Chinese cities, and much of the Dutch East Indies

In 1945, the Pacific War between the Empire of Japan and the Allies entered its fourth year. The Japanese fought fiercely, ensuring that U.S. victory would come at an enormous cost. Of the 1.25 million battle casualties incurred by the United States in World War II, including both military personnel killed in action and wounded in action, nearly one million occurred in the twelve-month period from June 1944 to June 1945. December 1944 saw American battle casualties hit an all-time monthly high of 88,000 as a result of the German Ardennes Offensive.[1] In the Pacific, the Allies returned to the Philippines,[2] recaptured Burma,[3] and invaded Borneo.[4] Offensives were undertaken to reduce the Japanese forces remaining in Bougainville, New Guinea and the Philippines.[5] In April 1945, American forces landed on Okinawa, where heavy fighting continued until June. Along the way, the ratio of Japanese to American casualties dropped from 5:1 in the Philippines to 2:1 on Okinawa.[1]

Although some Japanese were taken prisoner, most fought until they were killed or committed suicide. Nearly 99% of the 21,000 defenders of Iwo Jima were killed. Of the 117,000 Japanese troops defending Okinawa in April–June 1945, 94% were killed. American military leaders used these figures to estimate high casualties among American soldiers in the planned invasion of Japan.[6]

As the Allies advanced towards Japan, conditions became steadily worse for the Japanese people. Japan’s merchant fleet declined from 5,250,000 gross tons in 1941 to 1,560,000 tons in March 1945, and 557,000 tons in August 1945. Lack of raw materials forced the Japanese war economy into a steep decline after the middle of 1944. The civilian economy, which had slowly deteriorated throughout the war, reached disastrous levels by the middle of 1945. The loss of shipping also affected the fishing fleet, and the 1945 catch was only 22% of that in 1941. The 1945 rice harvest was the worst since 1909, and hunger and malnutrition became widespread. U.S. industrial production was overwhelmingly superior to Japan’s. By 1943, the U.S. produced almost 100,000 aircraft a year, compared to Japan’s production of 70,000 for the entire war. By the summer of 1944, the U.S. had almost a hundred aircraft carriers in the Pacific, far more than Japan’s twenty-five for the entire war. In February 1945, Prince Fumimaro Konoe advised the Emperor Hirohito that defeat was inevitable, and urged him to abdicate.[7]

Preparations to invade Japan

Even before the surrender of Nazi Germany on May 8, 1945, plans were under way for the largest operation of the Pacific War, Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan.[8] The operation had two parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet. Set to begin in October 1945, Olympic involved a series of landings by the U.S. Sixth Army intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū.[9] Operation Olympic was to be followed in March 1946 by Operation Coronet, the capture of the Kantō Plain, near Tokyo on the main Japanese island of Honshū by the U.S. First, Eighth and Tenth Armies, as well as a Commonwealth Corps made up of Australian, British and Canadian divisions. The target date was chosen to allow for Olympic to complete its objectives, for troops to be redeployed from Europe, and the Japanese winter to pass.[10]

Japan’s geography made this invasion plan obvious to the Japanese; they were able to predict the Allied invasion plans accurately and thus adjust their defensive plan, Operation Ketsugō, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations.[11] Four veteran divisions were withdrawn from the Kwantung Army in Manchuria in March 1945 to strengthen the forces in Japan,[12] and 45 new divisions were activated between February and May 1945. Most were immobile formations for coastal defense, but 16 were high quality mobile divisions.[13] In all, there were 2.3 million Japanese Army troops prepared to defend the home islands, backed by a civilian militia of 28 million men and women. Casualty predictions varied widely, but were extremely high. The Vice Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff, Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi, predicted up to 20 million Japanese deaths.[14]

A study from June 15, 1945, by the Joint War Plans Committee,[15] who provided planning information to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, estimated that Olympic would result in between 130,000 and 220,000 U.S. casualties, of which U.S. dead would be in the range from 25,000 to 46,000. Delivered on June 15, 1945, after insight gained from the Battle of Okinawa, the study noted Japan’s inadequate defenses due to the very effective sea blockade and the American firebombing campaign. The Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General of the Army George Marshall, and the Army Commander in Chief in the Pacific, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, signed documents agreeing with the Joint War Plans Committee estimate.[16]

The Americans were alarmed by the Japanese buildup, which was accurately tracked through Ultra intelligence.[17] Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was sufficiently concerned about high American estimates of probable casualties to commission his own study by Quincy Wright and William Shockley. Wright and Shockley spoke with Colonels James McCormack and Dean Rusk, and examined casualty forecasts by Michael E. DeBakey and Gilbert Beebe. Wright and Shockley estimated the invading Allies would suffer between 1.7 and 4 million casualties in such a scenario, of whom between 400,000 and 800,000 would be dead, while Japanese fatalities would have been around 5 to 10 million.[18][19]

Marshall began contemplating the use of a weapon which was “readily available and which assuredly can decrease the cost in American lives”:[20] poison gas. Quantities of phosgene, mustard gas, tear gas and cyanogen chloride were moved to Luzon from stockpiles in Australia and New Guinea in preparation for Operation Olympic, and MacArthur ensured that Chemical Warfare Service units were trained in their use.[20] Consideration was also given to using biological weapons against Japan.[21]

Air raids on Japan

While the United States had developed plans for an air campaign against Japan prior to the Pacific War, the capture of Allied bases in the western Pacific in the first weeks of the conflict meant that this offensive did not begin until mid-1944 when the long-ranged Boeing B-29 Superfortress became ready for use in combat.[22] Operation Matterhorn involved India-based B-29s staging through bases around Chengdu in China to make a series of raids on strategic targets in Japan.[23] This effort failed to achieve the strategic objectives that its planners had intended, largely because of logistical problems, the bomber’s mechanical difficulties, the vulnerability of Chinese staging bases, and the extreme range required to reach key Japanese cities.[24]

United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) Brigadier General Haywood S. Hansell determined that Guam, Tinian, and Saipan in the Mariana Islands would better serve as B-29 bases, but they were in Japanese hands.[25]Strategies were shifted to accommodate the air war,[26] and the islands were captured between June and August 1944. Air bases were developed,[27] and B-29 operations commenced from the Marianas in October 1944.[28]These bases were easily resupplied by cargo ships.[29] The XXI Bomber Command began missions against Japan on November 18, 1944.[30]

The early attempts to bomb Japan from the Marianas proved just as ineffective as the China-based B-29s had been. Hansell continued the practice of conducting so-called high-altitude precision bombing, aimed at key industries and transportation networks, even after these tactics had not produced acceptable results.[31] These efforts proved unsuccessful due to logistical difficulties with the remote location, technical problems with the new and advanced aircraft, unfavorable weather conditions, and enemy action.[32][33]

The Operation Meetinghousefirebombing of Tokyo on the night of March 9–10, 1945, was the single deadliest air raid in history;[34] with a greater area of fire damage and loss of life than the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima or Nagasaki as single events.[35][36]

Hansell’s successor, Major General Curtis LeMay, assumed command in January 1945 and initially continued to use the same precision bombing tactics, with equally unsatisfactory results. The attacks initially targeted key industrial facilities but much of the Japanese manufacturing process was carried out in small workshops and private homes.[37] Under pressure from USAAF headquarters in Washington, LeMay changed tactics and decided that low-level incendiary raids against Japanese cities were the only way to destroy their production capabilities, shifting from precision bombing to area bombardment with incendiaries.[38]

Like most strategic bombing during World War II, the aim of the USAAF offensive against Japan was to destroy the enemy’s war industries, kill or disable civilian employees of these industries, and undermine civilian morale. Civilians who took part in the war effort through such activities as building fortifications and manufacturing munitions and other war materials in factories and workshops were considered combatants in a legal sense and therefore liable to be attacked.[39][40]

Over the next six months, the XXI Bomber Command under LeMay firebombed 67 Japanese cities. The firebombing of Tokyo, codenamed Operation Meetinghouse, on March 9–10 killed an estimated 100,000 people and destroyed 16 square miles (41 km2) of the city and 267,000 buildings in a single night. It was the deadliest bombing raid of the war, at a cost of 20 B-29s shot down by flak and fighters.[41] By May, 75% of bombs dropped were incendiaries designed to burn down Japan’s “paper cities”. By mid-June, Japan’s six largest cities had been devastated.[42] The end of the fighting on Okinawa that month provided airfields even closer to the Japanese mainland, allowing the bombing campaign to be further escalated. Aircraft flying from Allied aircraft carriers and the Ryukyu Islands also regularly struck targets in Japan during 1945 in preparation for Operation Downfall.[43]Firebombing switched to smaller cities, with populations ranging from 60,000 to 350,000. According to Yuki Tanaka, the U.S. fire-bombed over a hundred Japanese towns and cities.[44] These raids were also devastating.[45]

The Japanese military was unable to stop the Allied attacks and the country’s civil defense preparations proved inadequate. Japanese fighters and antiaircraft guns had difficulty engaging bombers flying at high altitude.[46]From April 1945, the Japanese interceptors also had to face American fighter escorts based on Iwo Jima and Okinawa.[47] That month, the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service and Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service stopped attempting to intercept the air raids in order to preserve fighter aircraft to counter the expected invasion.[48] By mid-1945 the Japanese only occasionally scrambled aircraft to intercept individual B-29s conducting reconnaissance sorties over the country, in order to conserve supplies of fuel.[49] By July 1945, the Japanese had stockpiled 1,156,000 US barrels (137,800,000 l; 36,400,000 US gal; 30,300,000 imp gal) of avgas for the invasion of Japan.[50] While the Japanese military decided to resume attacks on Allied bombers from late June, by this time there were too few operational fighters available for this change of tactics to hinder the Allied air raids.[51]

Atomic bomb development

The discovery of nuclear fission by German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in 1938, and its theoretical explanation by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, made the development of an atomic bomb a theoretical possibility.[52] Fears that a German atomic bomb project would develop atomic weapons first, especially among scientists who were refugees from Nazi Germany and other fascist countries, were expressed in the Einstein-Szilard letter. This prompted preliminary research in the United States in late 1939.[53]Progress was slow until the arrival of the British MAUD Committee report in late 1941, which indicated that only 5–10 kilograms of isotopically enriched uranium-235 was needed for a bomb instead of tons of un-enriched uranium and a neutron moderator (e.g. heavy water).[54]

Working in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada, with their respective projects Tube Alloys and Chalk River Laboratories,[55][56] the Manhattan Project, under the direction of Major General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, designed and built the first atomic bombs.[57] Groves appointed J. Robert Oppenheimer to organize and head the project’s Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, where bomb design work was carried out.[58] Two types of bombs were eventually developed. Little Boy was a gun-type fission weapon that used uranium-235, a rare isotope of uranium separated at the Clinton Engineer Works at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.[59] The other, known as a Fat Man device (both types named by Robert Serber), was a more powerful and efficient, but more complicated, implosion-type nuclear weapon that used plutonium created in nuclear reactors at Hanford, Washington. A test implosion weapon, the gadget, was detonated at Trinity Site, on July 16, 1945, near Alamogordo, New Mexico.[60]

There was a Japanese nuclear weapon program, but it lacked the human, mineral and financial resources of the Manhattan Project, and never made much progress towards developing an atomic bomb.[61]

Preparations

Organization and training

Aircraft of the 509th Composite Group that took part in the Hiroshima bombing. Left to right: Big Stink, The Great Artiste, Enola Gay

The 509th Composite Group was constituted on December 9, 1944, and activated on December 17, 1944, at Wendover Army Air Field, Utah, commanded by Colonel Paul Tibbets.[62] Tibbets was assigned to organize and command a combat group to develop the means of delivering an atomic weapon against targets in Germany and Japan. Because the flying squadrons of the group consisted of both bomber and transport aircraft, the group was designated as a “composite” rather than a “bombardment” unit.[63]

Working with the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, Tibbets selected Wendover for his training base over Great Bend, Kansas, and Mountain Home, Idaho, because of its remoteness.[64] Each bombardier completed at least 50 practice drops of inert or conventional explosive pumpkin bombs and Tibbets declared his group combat-ready.[65]

The 509th Composite Group had an authorized strength of 225 officers and 1,542 enlisted men, almost all of whom eventually deployed to Tinian. In addition to its authorized strength, the 509th had attached to it on Tinian 51 civilian and military personnel from Project Alberta,[66] known as the 1st Technical Detachment.[67] The 509th Composite Group’s 393d Bombardment Squadron was equipped with 15 Silverplate B-29s. These aircraft were specially adapted to carry nuclear weapons, and were equipped with fuel-injected engines, Curtiss Electric reversible-pitch propellers, pneumatic actuators for rapid opening and closing of bomb bay doors and other improvements.[68]

The ground support echelon of the 509th Composite Group moved by rail on April 26, 1945, to its port of embarkation at Seattle, Washington. On May 6 the support elements sailed on the SS Cape Victory for the Marianas, while group materiel was shipped on the SS Emile Berliner. The Cape Victory made brief port calls at Honolulu and Eniwetok but the passengers were not permitted to leave the dock area. An advance party of the air echelon, consisting of 29 officers and 61 enlisted men flew by C-54 to North Field on Tinian, between May 15 and May 22.[69]

There were also two representatives from Washington, D.C., Brigadier General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, and Rear Admiral William R. Purnell of the Military Policy Committee,[70] who were on hand to decide higher policy matters on the spot. Along with Captain William S. Parsons, the commander of Project Alberta, they became known as the “Tinian Joint Chiefs”.[71]

Choice of targets

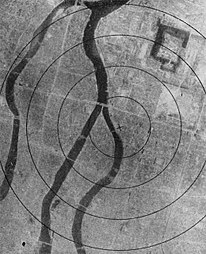

The mission runs of August 6 and 9, with Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Kokura (the original target for August 9) displayed.

General Thomas Handy‘s order to General Carl Spaatz authorizing the dropping of the atomic bombs

In April 1945, Marshall asked Groves to nominate specific targets for bombing for final approval by himself and Stimson. Groves formed a Target Committee, chaired by himself, that included Farrell, Major John A. Derry, Colonel William P. Fisher, Joyce C. Stearns and David M. Dennison from the USAAF; and scientists John von Neumann, Robert R. Wilson and William Penney from the Manhattan Project. The Target Committee met in Washington on April 27; at Los Alamos on May 10, where it was able to talk to the scientists and technicians there; and finally in Washington on May 28, where it was briefed by Tibbets and Commander Frederick Ashworth from Project Alberta, and the Manhattan Project’s scientific advisor, Richard C. Tolman.[72]

The Target Committee nominated five targets: Kokura, the site of one of Japan’s largest munitions plants; Hiroshima, an embarkation port and industrial center that was the site of a major military headquarters; Yokohama, an urban center for aircraft manufacture, machine tools, docks, electrical equipment and oil refineries; Niigata, a port with industrial facilities including steel and aluminum plants and an oil refinery; and Kyoto, a major industrial center. The target selection was subject to the following criteria:

- The target was larger than 3 mi (4.8 km) in diameter and was an important target in a large urban area.

- The blast would create effective damage.

- The target was unlikely to be attacked by August 1945.[73]

These cities were largely untouched during the nightly bombing raids and the Army Air Forces agreed to leave them off the target list so accurate assessment of the weapon could be made. Hiroshima was described as “an important army depot and port of embarkation in the middle of an urban industrial area. It is a good radar target and it is such a size that a large part of the city could be extensively damaged. There are adjacent hills which are likely to produce a focusing effect which would considerably increase the blast damage. Due to rivers it is not a good incendiary target.”[73]

The Target Committee stated that “It was agreed that psychological factors in the target selection were of great importance. Two aspects of this are (1) obtaining the greatest psychological effect against Japan and (2) making the initial use sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognized when publicity on it is released. Kyoto had the advantage of being an important center for military industry, as well an intellectual center and hence a population better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon. The Emperor’s palace in Tokyo has a greater fame than any other target but is of least strategic value.”[73]

Edwin O. Reischauer, a Japan expert for the U.S. Army Intelligence Service, was incorrectly said to have prevented the bombing of Kyoto.[73] In his autobiography, Reischauer specifically refuted this claim:

… the only person deserving credit for saving Kyoto from destruction is Henry L. Stimson, the Secretary of War at the time, who had known and admired Kyoto ever since his honeymoon there several decades earlier.[74] [75]

On May 30, Stimson asked Groves to remove Kyoto from the target list due to its historical, religious and cultural significance, but Groves pointed to its military and industrial significance.[76] Stimson then approached President Harry S. Truman about the matter. Truman agreed with Stimson, and Kyoto was temporarily removed from the target list.[77] Groves attempted to restore Kyoto to the target list in July, but Stimson remained adamant.[78][79] On July 25, Nagasaki was put on the target list in place of Kyoto.[79] Orders for the attack were issued to General Carl Spaatz on July 25 under the signature of General Thomas T. Handy, the acting Chief of Staff, since Marshall was at the Potsdam Conference with Truman.[80] That day, Truman noted in his diary that:

This weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th. I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop that terrible bomb on the old capital [Kyoto] or the new [Tokyo]. He and I are in accord. The target will be a purely military one.[81]

Proposed demonstration

In early May 1945, the Interim Committee was created by Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of Truman to advise on matters pertaining to nuclear energy.[82] During the meetings on May 31 and June 1, scientist Ernest Lawrence had suggested giving the Japanese a non-combat demonstration.[83] Arthur Compton later recalled that:

It was evident that everyone would suspect trickery. If a bomb were exploded in Japan with previous notice, the Japanese air power was still adequate to give serious interference. An atomic bomb was an intricate device, still in the developmental stage. Its operation would be far from routine. If during the final adjustments of the bomb the Japanese defenders should attack, a faulty move might easily result in some kind of failure. Such an end to an advertised demonstration of power would be much worse than if the attempt had not been made. It was now evident that when the time came for the bombs to be used we should have only one of them available, followed afterwards by others at all-too-long intervals. We could not afford the chance that one of them might be a dud. If the test were made on some neutral territory, it was hard to believe that Japan’s determined and fanatical military men would be impressed. If such an open test were made first and failed to bring surrender, the chance would be gone to give the shock of surprise that proved so effective. On the contrary, it would make the Japanese ready to interfere with an atomic attack if they could. Though the possibility of a demonstration that would not destroy human lives was attractive, no one could suggest a way in which it could be made so convincing that it would be likely to stop the war.[84]

The possibility of a demonstration was raised again in the Franck Report issued by physicist James Franck on June 11 and the Scientific Advisory Panel rejected his report on June 16, saying that “we can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war; we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.” Franck then took the report to Washington, D.C., where the Interim Committee met on June 21 to re-examine its earlier conclusions; but it reaffirmed that there was no alternative to the use of the bomb on a military target.[85]

Like Compton, many U.S. officials and scientists argued that a demonstration would sacrifice the shock value of the atomic attack, and the Japanese could deny the atomic bomb was lethal, making the mission less likely to produce surrender. Allied prisoners of war might be moved to the demonstration site and be killed by the bomb. They also worried that the bomb might be a dud since the Trinity test was of a stationary device, not an air-dropped bomb. In addition, only two bombs would be available at the start of August, although more were in production, and they cost billions of dollars, so using one for a demonstration would be expensive.[86][87]

Leaflets

Various leaflets were dropped on Japan, three versions showing the names of 11 or 12 Japanese cities targeted for destruction by firebombing. The other side contained text stating “…we cannot promise that only these cities will be among those attacked …”[88]

For several months, the U.S. had dropped more than 63 million leaflets across Japan warning civilians of air raids. Many Japanese cities suffered terrible damage from aerial bombings; some were as much as 97% destroyed. LeMay thought that leaflets would increase the psychological impact of bombing, and reduce the international stigma of area-bombing cities. Even with the warnings, Japanese opposition to the war remained ineffective. In general, the Japanese regarded the leaflet messages as truthful with many Japanese choosing to leave major cities, the leaflets caused such concern amongst the Empire of Japan that they ordered for anyone caught in possession of a leaflet to be arrested.[88][89] Leaflet texts were prepared by recent Japanese prisoners of war because they were thought to be the best choice “to appeal to their compatriots”.[90]

In preparation for dropping an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the Oppenheimer led Scientific Panel of the Interim Committee decided against a demonstration bomb, and against a special leaflet warning, in both cases because of the likelihood of being shot out of the sky, uncertainty of a successful detonation, and the wish to maximize shock in the leadership.[91] No warning was given to Hiroshima that a new and much more destructive bomb was going to be dropped.[92] Various sources give conflicting information about when the last leaflets were dropped on Hiroshima prior to the atomic bomb. Robert Jay Lifton writes that it was July 27,[92] and Theodore H. McNelly that it was July 3.[91] The USAAF history notes eleven cities were targeted with leaflets on July 27, but Hiroshima was not one of them, and there were no leaflet sorties on July 30.[89] Leaflet sorties were undertaken on August 1 and August 4. Hiroshima may have been leafleted in late July or early August, as survivor accounts talk about a delivery of leaflets a few days before the atomic bomb was dropped.[92] Three versions were printed of a leaflet listing 11 or 12 cities targeted for firebombing; a total of 33 cities listed. With the text of this leaflet reading in Japanese “…we cannot promise that only these cities will be among those attacked…”[88] Hiroshima is not listed.[93][94][95][96]

Potsdam Declaration

Truman delayed the start of the summit by two weeks in the hope that the bomb could be tested before the start of negotiations with Stalin. The successful Trinity Test of July 16 exceeded expectations. On July 26, Allied leaders issued the Potsdam Declaration outlining terms of surrender for Japan. It was presented as an ultimatum and stated that without a surrender, the Allies would attack Japan, resulting in “the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland”. The atomic bomb was not mentioned in the communiqué. On July 28, Japanese papers reported that the declaration had been rejected by the Japanese government. That afternoon, Prime Minister Suzuki Kantarō declared at a press conference that the Potsdam Declaration was no more than a rehash (yakinaoshi) of the Cairo Declaration and that the government intended to ignore it (mokusatsu, “kill by silence”).[97] The statement was taken by both Japanese and foreign papers as a clear rejection of the declaration. Emperor Hirohito, who was waiting for a Soviet reply to non-committal Japanese peace feelers, made no move to change the government position.[98] Japan’s willingness to surrender remained conditional on the preservation of the imperial institution; that Japan not be occupied; that the Japanese armed forces be disbanded voluntarily; and that war criminals be prosecuted by Japanese courts.[99]

Under the 1943 Quebec Agreement with the United Kingdom, the United States had agreed that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without mutual consent. In June 1945 the head of the British Joint Staff Mission, Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, agreed that the use of nuclear weapons against Japan would be officially recorded as a decision of the Combined Policy Committee.[100] At Potsdam, Truman agreed to a request from Winston Churchill that Britain be represented when the atomic bomb was dropped. William Penney and Group Captain Leonard Cheshire were sent to Tinian, but found that LeMay would not let them accompany the mission. All they could do was send a strongly worded signal back to Wilson.[101]

Bombs

The Little Boy bomb, except for the uranium payload, was ready at the beginning of May 1945.[102] The uranium-235 projectile was completed on June 15, and the target on July 24.[103] The target and bomb pre-assemblies (partly assembled bombs without the fissile components) left Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, California, on July 16 aboard the cruiser USS Indianapolis, arriving July 26.[104] The target inserts followed by air on July 30.[103]

The first plutonium core, along with its polonium–beryllium urchin initiator, was transported in the custody of Project Alberta courier Raemer Schreiber in a magnesium field carrying case designed for the purpose by Philip Morrison. Magnesium was chosen because it does not act as a tamper.[105] The core departed from Kirtland Army Air Field on a C-54 transport aircraft of the 509th Composite Group’s 320th Troop Carrier Squadron on July 26, and arrived at North Field July 28. Three Fat Man high-explosive pre-assemblies, designated F31, F32, and F33, were picked up at Kirtland on July 28 by three B-29s, from the 393d Bombardment Squadron, plus one from the 216th Army Air Force Base Unit, and transported to North Field, arriving on August 2.[106]

Hiroshima

Hiroshima during World War II

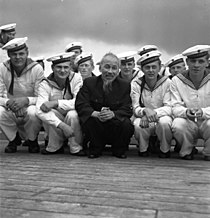

The Enola Gay dropped the “Little Boy” atomic bomb on Hiroshima. In this photograph are five of the aircraft’s ground crew with mission commander Paul Tibbets in the center.

At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of both industrial and military significance. A number of military units were located nearby, the most important of which was the headquarters of Field Marshal Shunroku Hata‘s Second General Army, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan,[107] and was located in Hiroshima Castle. Hata’s command consisted of some 400,000 men, most of whom were on Kyushu where an Allied invasion was correctly anticipated.[108] Also present in Hiroshima were the headquarters of the 59th Army, the 5th Division and the 224th Division, a recently formed mobile unit.[109] The city was defended by five batteries of 7-cm and 8-cm (2.8 and 3.1 inch) anti-aircraft guns of the 3rd Anti-Aircraft Division, including units from the 121st and 122nd Anti-Aircraft Regiments and the 22nd and 45th Separate Anti-Aircraft Battalions. In total, an estimated 40,000 Japanese military personnel were stationed in the city.[110]

Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military, but it also had large stockpiles of military supplies.[111] The city was also a communications center, a key port for shipping and an assembly area for troops.[76] It was a beehive of war industry, manufacturing parts for planes and boats, for bombs, rifles, and handguns; children were shown how to construct and hurl gasoline bombs and the wheelchair-bound and bedridden were assembling booby traps to be planted in the beaches of Kyushu. A new slogan appeared on the walls of Hiroshima: “FORGET SELF! ALL OUT FOR YOUR COUNTRY!”[112] It was also the second largest city in Japan after Kyoto that was still undamaged by air raids,[113] due to the fact that it lacked the aircraft manufacturing industry that was the XXI Bomber Command’s priority target. On July 3, the Joint Chiefs of Staff placed it off limits to bombers, along with Kokura, Niigata and Kyoto.[114]

The center of the city contained several reinforced concrete buildings and lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small timber-made workshops set among Japanese houses. A few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were constructed of timber with tile roofs, and many of the industrial buildings were also built around timber frames. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage.[115]

The population of Hiroshima had reached a peak of over 381,000 earlier in the war but prior to the atomic bombing, the population had steadily decreased because of a systematic evacuation ordered by the Japanese government. At the time of the attack, the population was approximately 340,000–350,000.[116] Residents wondered why Hiroshima had been spared destruction by firebombing.[117] Some speculated that the city was to be saved for U.S. occupation headquarters, others thought perhaps their relatives in Hawaii and California had petitioned the U.S. government to avoid bombing Hiroshima.[118] More realistic city officials had ordered buildings torn down to create long, straight firebreaks, beginning in 1944.[119] Firebreaks continued to be expanded and extended up to the morning of August 6, 1945.[120]

Bombing of Hiroshima

Picture found in Honkawa Elementary School in 2013 of the Hiroshima atom bomb cloud, stated by some books and the Hiroshima Peace Museum as having been taken about 30 minutes after detonation from about 10 km (6.2 mi) east of the hypocenter. However experience on how quickly such clouds dissipate and comparisons to other photos puts this frame at 2-3 minutes after detonation, not 30 minutes.[121]

Hiroshima was the primary target of the first nuclear bombing mission on August 6, with Kokura and Nagasaki as alternative targets. Having been fully briefed under the terms of Operations Order No. 35, the 393d Bombardment Squadron B-29 Enola Gay, piloted by Tibbets, took off from North Field, Tinian, about six hours’ flight time from Japan. The Enola Gay (named after Tibbets’ mother) was accompanied by two other B-29s. The Great Artiste, commanded by Major Charles Sweeney, carried instrumentation, and a then-nameless aircraft later called Necessary Evil, commanded by Captain George Marquardt, served as the photography aircraft.[122]

| Aircraft | Pilot | Call Sign | Mission role |

| Straight Flush | Major Claude R. Eatherly | Dimples 85 | Weather reconnaissance (Hiroshima) |

| Jabit III | Major John A. Wilson | Dimples 71 | Weather reconnaissance (Kokura) |

| Full House | Major Ralph R. Taylor | Dimples 83 | Weather reconnaissance (Nagasaki) |

| Enola Gay | Colonel Paul W. Tibbets | Dimples 82 | Weapon delivery |

| The Great Artiste | Major Charles W. Sweeney | Dimples 89 | Blast measurement instrumentation |

| Necessary Evil | Captain. George W. Marquardt | Dimples 91 | Strike observation and photography |

| Top Secret | Captain Charles F. McKnight | Dimples 72 | Strike spare—did not complete mission |

After leaving Tinian the aircraft made their way separately to Iwo Jima to rendezvous with Sweeney and Marquardt at 05:55 at 9,200 feet (2,800 m),[124] and set course for Japan. The aircraft arrived over the target in clear visibility at 31,060 feet (9,470 m).[125] Parsons, who was in command of the mission, armed the bomb during the flight to minimize the risks during takeoff. He had witnessed four B-29s crash and burn at takeoff, and feared that a nuclear explosion would occur if a B-29 crashed with an armed Little Boy on board.[126] His assistant, Second Lieutenant Morris R. Jeppson, removed the safety devices 30 minutes before reaching the target area.[127]

During the night of August 5–6, Japanese early warning radar detected the approach of numerous American aircraft headed for the southern part of Japan. Radar detected 65 bombers headed for Saga, 102 bound for Maebashi, 261 en route to Nishinomiya, 111 headed for Ube and 66 bound for Imabari. An alert was given and radio broadcasting stopped in many cities, among them Hiroshima. The all-clear was sounded in Hiroshima at 00:05.[128] About an hour before the bombing, the air raid alert was sounded again, as Straight Flush flew over the city. It broadcast a short message which was picked up by Enola Gay. It read: “Cloud cover less than 3/10th at all altitudes. Advice: bomb primary.”[129] The all-clear was sounded over Hiroshima again at 07:09.[130]

At 08:09, Tibbets started his bomb run and handed control over to his bombardier, Major Thomas Ferebee.[131] The release at 08:15 (Hiroshima time) went as planned, and the Little Boy containing about 64 kg (141 lb) of uranium-235 took 44.4 seconds to fall from the aircraft flying at about 31,000 feet (9,400 m) to a detonation height of about 1,900 feet (580 m) above the city.[132][133] Enola Gay traveled 11.5 mi (18.5 km) before it felt the shock waves from the blast.[134]

For decades this “Hiroshima strike” photo was misidentified as the mushroom cloud of the bomb that formed at c. 08:16.[135][136] However, due to its much greater height, the scene was identified by a researcher in March 2016 as the firestorm-cloud that engulfed the city,[136] a fire that reached its peak intensity some three hours after the bomb.[137] The image with the incorrect description featured prominently in the Hiroshima Peace Museum up to 2016,[136] though not cited, it had much earlier, also been mis-attributed and presented to the public in 1955 by US artists, with the world-touring The Family of Man exhibition. Without knowledge of the photo the output of energy from the fuel in the city, necessary to loft a stratospheric firestorm-cloud, had been estimated as 1000 times the energy of the bomb.[137] Post March estimates using the height of this Hiroshima-cloud also point at the underlying firestorm releasing approximately 1000 times the energy of the bomb.[136] Twenty minutes after detonation, during the formation of this firestorm, soot filled black rain began to fall on survivors.[138] Scientist Alan Robock suggests that 100 of these firestorm-clouds would create a small “nuclear winter“, 1-2 C of global cooling.[139]

Due to crosswind, the bomb missed the aiming point, the Aioi Bridge, by approximately 800 ft (240 m) and detonated directly over Shima Surgical Clinic[140] at 34.39468°N 132.45462°E. It created a blast equivalent to 16 kilotons of TNT (67 TJ), ± 2 kt.[132] The weapon was considered very inefficient, with only 1.7% of its material fissioning.[141] The radius of total destruction was about 1 mile (1.6 km), with resulting fires across 4.4 square miles (11 km2).[142]

People on the ground reported seeing a pika or brilliant flash of light followed by a don, a loud booming sound.[143] Some 70,000–80,000 people, of whom 20,000 were Japanese soldiers and 20,000 Korean slave laborers, or around 30% of the population of Hiroshima, were killed by the blast and resultant firestorm,[144][145] and another 70,000 injured.[146]

Enola Gay stayed over the target area for two minutes and was ten miles away when the bomb detonated. Only Tibbets, Parsons, and Ferebee knew of the nature of the weapon; the others on the bomber were only told to expect a blinding flash and given black goggles. “It was hard to believe what we saw”, Tibbets told reporters, while Parsons said “the whole thing was tremendous and awe-inspiring … the men aboard with me gasped ‘My God'”. He and Tibbets compared the shockwave to “a close burst of ack-ack fire”.[147]

Events on the ground

Some of the reinforced concrete buildings in Hiroshima had been very strongly constructed because of the earthquake danger in Japan, and their framework did not collapse even though they were fairly close to the blast center. Since the bomb detonated in the air, the blast was directed more downward than sideways, which was largely responsible for the survival of the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, now commonly known as the Genbaku (A-bomb) dome. This building was designed and built by the Czech architect Jan Letzel, and was only 150 m (490 ft) from ground zero. The ruin was named Hiroshima Peace Memorial and was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 over the objections of the United States and China, which expressed reservations on the grounds that other Asian nations were the ones who suffered the greatest loss of life and property, and a focus on Japan lacked historical perspective.[148]

The US surveys estimated that 4.7 square miles (12 km2) of the city were destroyed. Japanese officials determined that 69% of Hiroshima’s buildings were destroyed and another 6–7% damaged.[149] The bombing started fires that spread rapidly through timber and paper homes. As in other Japanese cities, the firebreaks proved ineffective.[150]

| Hiroshima bombing | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eizō Nomura was the closest known survivor, who was in the basement of a reinforced concrete building (it remained as the Rest House after the war) only 170 metres (560 ft) from ground zero (the hypocenter) at the time of the attack.[151][152] He lived into his 80s.[153][154] Akiko Takakura was among the closest survivors to the hypocenter of the blast. She had been in the solidly built Bank of Hiroshima only 300 meters (980 ft) from ground-zero at the time of the attack.[155]

Over 90% of the doctors and 93% of the nurses in Hiroshima were killed or injured—most had been in the downtown area which received the greatest damage.[156] The hospitals were destroyed or heavily damaged. Only one doctor, Terufumi Sasaki, remained on duty at the Red Cross Hospital.[150] Nonetheless, by early afternoon, the police and volunteers had established evacuation centres at hospitals, schools and tram stations, and a morgue was established in the Asano library.[157]

Most elements of the Japanese Second General Army headquarters were at physical training on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle, barely 900 yards (820 m) from the hypocenter. The attack killed 3,243 troops on the parade ground.[158] The communications room of Chugoku Military District Headquarters that was responsible for issuing and lifting air raid warnings was in a semi-basement in the castle. Yoshie Oka, a Hijiyama Girls High School student who had been conscripted/mobilized to serve as a communications officer had just sent a message that the alarm had been issued for Hiroshima and neighboring Yamaguchi, when the bomb exploded. She used a special phone to inform[better source needed] Fukuyama Headquarters (some 100 km away) that “Hiroshima has been attacked by a new type of bomb. The city is in a state of near-total destruction.”[159]

Since Mayor Senkichi Awaya had been killed while eating breakfast with his son and granddaughter at the mayoral residence, Field Marshal Hata, who was only slightly wounded, took over the administration of the city, and coordinated relief efforts. Many of his staff had been killed or fatally wounded, including a Korean prince of the Joseon Dynasty, Yi Wu, who was serving as a lieutenant colonel in the Japanese Army.[160][161] Hata’s senior surviving staff officer was the wounded Colonel Kumao Imoto, who acted as his chief of staff. Soldiers from the undamaged Hiroshima Ujina Harbor used suicide boats, intended to repel the American invasion, to collect the wounded and take them down the rivers to the military hospital at Ujina.[162] Trucks and trains brought in relief supplies and evacuated survivors from the city.[163]

Twelve American airmen were imprisoned at the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters located about 1,300 feet (400 m) from the hypocenter of the blast.[164] Most died instantly, although two were reported to have been executed by their captors, and two prisoners badly injured by the bombing were left next to the Aioi Bridge by the Kempei Tai, where they were stoned to death.[165] Eight U.S. prisoners of war killed as part of the medical experiments program at Kyushu University were falsely reported by Japanese authorities as having been killed in the atomic blast as part an attempted cover up.[166]

Japanese realization of the bombing

The Tokyo control operator of the Japan Broadcasting Corporation noticed that the Hiroshima station had gone off the air. He tried to re-establish his program by using another telephone line, but it too had failed.[167] About 20 minutes later the Tokyo railroad telegraph center realized that the main line telegraph had stopped working just north of Hiroshima. From some small railway stops within 16 km (10 mi) of the city came unofficial and confused reports of a terrible explosion in Hiroshima. All these reports were transmitted to the headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff.[168]

Military bases repeatedly tried to call the Army Control Station in Hiroshima. The complete silence from that city puzzled the General Staff; they knew that no large enemy raid had occurred and that no sizable store of explosives was in Hiroshima at that time. A young officer was instructed to fly immediately to Hiroshima, to land, survey the damage, and return to Tokyo with reliable information for the staff. It was felt that nothing serious had taken place and that the explosion was just a rumor.[168]

The staff officer went to the airport and took off for the southwest. After flying for about three hours, while still nearly 160 km (100 mi) from Hiroshima, he and his pilot saw a great cloud of smoke from the bomb. After circling the city in order to survey the damage they landed south of the city, where the staff officer, after reporting to Tokyo, began to organize relief measures. Tokyo’s first indication that the city had been destroyed by a new type of bomb came from President Truman’s announcement of the strike, sixteen hours later.[168]

Events of August 7–9

Leaflet AB12,[169] with information on the Hiroshima bomb and a warning to civilians to petition the Emperor to surrender was dropped over Japan beginning on August 9,[169] by the 509th Composite Group on the bombing mission. Although it is not identified by them, an AB11 is in the possession of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.[170] By August 8,[171] the 50,000-watt standard wave station on Saipan the OWI radio station, broadcast a similar message to Japan every 15 minutes about Hiroshima, stating that more Japanese cities would face a similar fate in the absence of immediate acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration and emphatically urged civilians to evacuate major cities. Radio Japan, which continued to extoll victory for Japan by never surrendering,[88] had informed the Japanese of the destruction of Hiroshima by a single bomb.[172]

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

After the Hiroshima bombing, Truman issued a statement announcing the use of the new weapon. He stated, “We may be grateful to Providence” that the German atomic bomb project had failed, and that the United States and its allies had “spent two billion dollars on the greatest scientific gamble in history—and won”. Truman then warned Japan: “If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.”[173]

This was a widely broadcast speech picked up by Japanese news agencies.[174] As a result, Prime Minister Suzuki felt compelled to meet the Japanese press, to whom he reiterated his government’s commitment to ignore the Allies’ demands and fight on.[175]

The Japanese government did not react. Emperor Hirohito, the government, and the war council considered four conditions for surrender: the preservation of the kokutai (Imperial institution and national polity), assumption by the Imperial Headquarters of responsibility for disarmament and demobilization, no occupation of the Japanese Home Islands, Korea, or Formosa, and delegation of the punishment of war criminals to the Japanese government.[176]

Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov informed Tokyo of the Soviet Union’s unilateral abrogation of the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact on August 5. At two minutes past midnight on August 9, Tokyo time, Soviet infantry, armor, and air forces had launched the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation.[177] Four hours later, word reached Tokyo of the Soviet Union’s official declaration of war. The senior leadership of the Japanese Army began preparations to impose martial law on the nation, with the support of Minister of War Korechika Anami, in order to stop anyone attempting to make peace.[178]

On August 7, a day after Hiroshima was destroyed, Dr. Yoshio Nishina and other atomic physicists arrived at the city, and carefully examined the damage. They then went back to Tokyo and told the cabinet that Hiroshima was indeed destroyed by an atomic bomb. Admiral Soemu Toyoda, the Chief of the Naval General Staff, estimated that no more than one or two additional bombs could be readied, so they decided to endure the remaining attacks, acknowledging “there would be more destruction but the war would go on”.[179] American Magic codebreakers intercepted the cabinet’s messages.[180]

Purnell, Parsons, Tibbets, Spaatz, and LeMay met on Guam that same day to discuss what should be done next.[181] Since there was no indication of Japan surrendering,[180] they decided to proceed with dropping another bomb. Parsons said that Project Alberta would have it ready by August 11, but Tibbets pointed to weather reports indicating poor flying conditions on that day due to a storm, and asked if the bomb could be readied by August 9. Parsons agreed to try to do so.[182][181]

Nagasaki

Nagasaki during World War II

The city of Nagasaki had been one of the largest seaports in southern Japan, and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials. The four largest companies in the city were Mitsubishi Shipyards, Electrical Shipyards, Arms Plant, and Steel and Arms Works, which employed about 90% of the city’s labor force, and accounted for 90% of the city’s industry.[183] Although an important industrial city, Nagasaki had been spared from firebombing because its geography made it difficult to locate at night with AN/APQ-13 radar.[114]

Unlike the other target cities, Nagasaki had not been placed off limits to bombers by the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s July 3 directive,[114][184] and was bombed on a small scale five times. During one of these raids on August 1, a number of conventional high-explosive bombs were dropped on the city. A few hit the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, and several hit the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works.[183] By early August, the city was defended by the 134th Anti-Aircraft Regiment of the 4th Anti-Aircraft Division with four batteries of 7 cm (2.8 in) anti-aircraft guns and two searchlight batteries.[110]

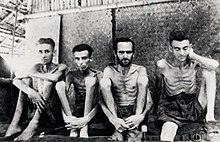

In contrast to Hiroshima, almost all of the buildings were of old-fashioned Japanese construction, consisting of timber or timber-framed buildings with timber walls (with or without plaster) and tile roofs. Many of the smaller industries and business establishments were also situated in buildings of timber or other materials not designed to withstand explosions. Nagasaki had been permitted to grow for many years without conforming to any definite city zoning plan; residences were erected adjacent to factory buildings and to each other almost as closely as possible throughout the entire industrial valley. On the day of the bombing, an estimated 263,000 people were in Nagasaki, including 240,000 Japanese residents, 10,000 Korean residents, 2,500 conscripted Korean workers, 9,000 Japanese soldiers, 600 conscripted Chinese workers, and 400 Allied prisoners of war in a camp to the north of Nagasaki.[185][186]

Bombing of Nagasaki

Responsibility for the timing of the second bombing was delegated to Tibbets. Scheduled for August 11 against Kokura, the raid was moved earlier by two days to avoid a five-day period of bad weather forecast to begin on August 10.[187] Three bomb pre-assemblies had been transported to Tinian, labeled F-31, F-32, and F-33 on their exteriors. On August 8, a dress rehearsal was conducted off Tinian by Sweeney using Bockscar as the drop airplane. Assembly F-33 was expended testing the components and F-31 was designated for the August 9 mission.[188]

| Aircraft | Pilot | Call Sign | Mission role |

| Enola Gay | Captain George W. Marquardt | Dimples 82 | Weather reconnaissance (Kokura) |

| Laggin’ Dragon | Captain Charles F. McKnight | Dimples 95 | Weather reconnaissance (Nagasaki) |

| Bockscar | Major Charles W. Sweeney | Dimples 77 | Weapon Delivery |

| The Great Artiste | Captain Frederick C. Bock | Dimples 89 | Blast measurement instrumentation |

| Big Stink | Major James I. Hopkins, Jr. | Dimples 90 | Strike observation and photography |

| Full House | Major Ralph R. Taylor | Dimples 83 | Strike spare—did not complete mission |

At 03:49 on the morning of August 9, 1945, Bockscar, flown by Sweeney’s crew, carried Fat Man, with Kokura as the primary target and Nagasaki the secondary target. The mission plan for the second attack was nearly identical to that of the Hiroshima mission, with two B-29s flying an hour ahead as weather scouts and two additional B-29s in Sweeney’s flight for instrumentation and photographic support of the mission. Sweeney took off with his weapon already armed but with the electrical safety plugs still engaged.[190]

During pre-flight inspection of Bockscar, the flight engineer notified Sweeney that an inoperative fuel transfer pump made it impossible to use 640 US gallons (2,400 l; 530 imp gal) of fuel carried in a reserve tank. This fuel would still have to be carried all the way to Japan and back, consuming still more fuel. Replacing the pump would take hours; moving the Fat Man to another aircraft might take just as long and was dangerous as well, as the bomb was live. Tibbets and Sweeney therefore elected to have Bockscar continue the mission.[191][192]

This time Penney and Cheshire were allowed to accompany the mission, flying as observers on the third plane, Big Stink, flown by the group’s operations officer, Major James I. Hopkins, Jr. Observers aboard the weather planes reported both targets clear. When Sweeney’s aircraft arrived at the assembly point for his flight off the coast of Japan, Big Stink failed to make the rendezvous.[190] According to Cheshire, Hopkins was at varying heights including 9,000 feet (2,700 m) higher than he should have been, and was not flying tight circles over Yakushima as previously agreed with Sweeney and Captain Frederick C. Bock, who was piloting the support B-29 The Great Artiste. Instead, Hopkins was flying 40-mile (64 km) dogleg patterns.[193] Though ordered not to circle longer than fifteen minutes, Sweeney continued to wait for Big Stink, at the urging of Ashworth, the plane’s weaponeer, who was in command of the mission.[194]

After exceeding the original departure time limit by a half-hour, Bockscar, accompanied by The Great Artiste, proceeded to Kokura, thirty minutes away. The delay at the rendezvous had resulted in clouds and drifting smoke over Kokura from fires started by a major firebombing raid by 224 B-29s on nearby Yahata the previous day. Additionally, the Yawata Steel Works intentionally burned coal tar, to produce black smoke.[195] The clouds and smoke resulted in 70% of the area over Kokura being covered, obscuring the aiming point. Three bomb runs were made over the next 50 minutes, burning fuel and exposing the aircraft repeatedly to the heavy defenses of Yawata, but the bombardier was unable to drop visually. By the time of the third bomb run, Japanese antiaircraft fire was getting close, and Second Lieutenant Jacob Beser, who was monitoring Japanese communications, reported activity on the Japanese fighter direction radio bands.[196]

After three runs over the city, and with fuel running low because of the failed fuel pump, they headed for their secondary target, Nagasaki.[190] Fuel consumption calculations made en route indicated that Bockscar had insufficient fuel to reach Iwo Jima and would be forced to divert to Okinawa, which had become entirely Allied-occupied territory only six weeks earlier. After initially deciding that if Nagasaki were obscured on their arrival the crew would carry the bomb to Okinawa and dispose of it in the ocean if necessary, Ashworth ruled that a radar approach would be used if the target was obscured.[197]

At about 07:50 Japanese time, an air raid alert was sounded in Nagasaki, but the “all clear” signal was given at 08:30. When only two B-29 Superfortresses were sighted at 10:53, the Japanese apparently assumed that the planes were only on reconnaissance and no further alarm was given.[198]

A few minutes later at 11:00, The Great Artiste dropped instruments attached to three parachutes. These instruments also contained an unsigned letter to Professor Ryokichi Sagane, a physicist at the University of Tokyo who studied with three of the scientists responsible for the atomic bomb at the University of California, Berkeley, urging him to tell the public about the danger involved with these weapons of mass destruction. The messages were found by military authorities but not turned over to Sagane until a month later.[199] In 1949, one of the authors of the letter, Luis Alvarez, met with Sagane and signed the document.[200]

At 11:01, a last-minute break in the clouds over Nagasaki allowed Bockscar‘s bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, to visually sight the target as ordered. The Fat Man weapon, containing a core of about 6.4 kg (14 lb) of plutonium, was dropped over the city’s industrial valley at 32.77372°N 129.86325°E. It exploded 47 seconds later at 1,650 ± 33 ft (503 ± 10 m), above a tennis court[201] halfway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Nagasaki Arsenal in the north. This was nearly 3 km (1.9 mi) northwest of the planned hypocenter; the blast was confined to the Urakami Valley and a major portion of the city was protected by the intervening hills.[202] The resulting explosion had a blast yield equivalent to 21 ± 2 kt (87.9 ± 8.4 TJ).[132] The explosion generated temperatures inside the fireball estimated at 3,900 °C (7,050 °F)[when?] and winds that were estimated at over 1,000 km/h (620 mph)[where?].[203][204]

Big Stink spotted the explosion from a hundred miles away, and flew over to observe.[205] Because of the delays in the mission and the inoperative fuel transfer pump, Bockscar did not have sufficient fuel to reach the emergency landing field at Iwo Jima, so Sweeney and Bock flew to Okinawa. Arriving there, Sweeney circled for 20 minutes trying to contact the control tower for landing clearance, finally concluding that his radio was faulty. Critically low on fuel, Bockscar barely made it to the runway on Okinawa’s Yontan Airfield. With enough fuel for only one landing attempt, Sweeney and Albury brought Bockscar in at 150 miles per hour (240 km/h) instead of the normal 120 miles per hour (190 km/h), firing distress flares to alert the field of the uncleared landing. The number two engine died from fuel starvation as Bockscar began its final approach. Touching the runway hard, the heavy B-29 slewed left and towards a row of parked B-24 bombers before the pilots managed to regain control. The B-29’s reversible propellers were insufficient to slow the aircraft adequately, and with both pilots standing on the brakes, Bockscar made a swerving 90-degree turn at the end of the runway to avoid running off the runway. A second engine died from fuel exhaustion by the time the plane came to a stop. The flight engineer later measured fuel in the tanks and concluded that less than five minutes total remained.[206]

Following the mission, there was confusion over the identification of the plane. The first eyewitness account by war correspondent William L. Laurence of The New York Times, who accompanied the mission aboard the aircraft piloted by Bock, reported that Sweeney was leading the mission in The Great Artiste. He also noted its “Victor” number as 77, which was that of Bockscar.[207] Laurence had interviewed Sweeney and his crew, and was aware that they referred to their airplane as The Great Artiste. Except for Enola Gay, none of the 393d’s B-29s had yet had names painted on the noses, a fact which Laurence himself noted in his account. Unaware of the switch in aircraft, Laurence assumed Victor 77 was The Great Artiste,[208] which was in fact, Victor 89.[209]

Events on the ground

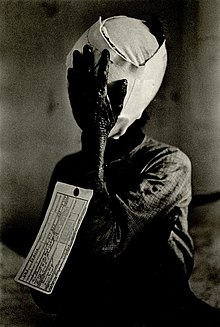

A photograph of Sumiteru Taniguchi‘s back injuries taken in January 1946 by a U.S. Marine photographer

Although the bomb was more powerful than the one used on Hiroshima, the effect was confined by hillsides to the narrow Urakami Valley.[210] Of 7,500 Japanese employees who worked inside the Mitsubishi Munitions plant, including “mobilized”/conscripted students and regular workers, 6,200 were killed. Some 17,000–22,000 others who worked in other war plants and factories in the city died as well.[211] Casualty estimates for immediate deaths vary widely, ranging from 22,000 to 75,000[211] At least 35,000–40,000 people were killed and 60,000 others injured.[212][213][214][215] In the days and months following the explosion, more people died from bomb effects. Because of the presence of undocumented foreign workers, and a number of military personnel in transit, there are great discrepancies in the estimates of total deaths by the end of 1945; a range of 39,000 to 80,000 can be found in various studies.[116][215]

Urakami Tenshudo (Catholic Church in Nagasaki) destroyed by the bomb, the dome/bell of the church, at right, having toppled off.

Unlike Hiroshima’s military death toll, only 150 Japanese soldiers were killed instantly, including thirty-six from the 134th AAA Regiment of the 4th AAA Division.[110][216] At least eight known POWs died from the bombing and as many as 13 may have died, including a British citizen, Royal Air Force Corporal Ronald Shaw,[217] and seven Dutch POWs.[218] One American POW, Joe Kieyoomia, was in Nagasaki at the time of the bombing but survived, reportedly having been shielded from the effects of the bomb by the concrete walls of his cell.[219] There were 24 Australian POWs in Nagasaki, all of whom survived.[220]

The radius of total destruction was about 1 mi (1.6 km), followed by fires across the northern portion of the city to 2 mi (3.2 km) south of the bomb.[142][221] About 58% of the Mitsubishi Arms Plant was damaged, and about 78% of the Mitsubishi Steel Works. The Mitsubishi Electric Works suffered only 10% structural damage as it was on the border of the main destruction zone. The Nagasaki Arsenal was destroyed in the blast.[222]

Although many fires likewise burnt following the bombing, in contrast to Hiroshima where sufficient fuel density was available, no firestorm developed in Nagasaki as the damaged areas did not furnish enough fuel to generate the phenomenon. Instead, the ambient wind at the time pushed the fire spread along the valley.[223]

Plans for more atomic attacks on Japan

The Nagasaki Prefecture Report on the bombing characterized Nagasaki as “like a graveyard with not a tombstone standing”[224]

Groves expected to have another atomic bomb ready for use on August 19, with three more in September and a further three in October.[87] On August 10, he sent a memorandum to Marshall in which he wrote that “the next bomb … should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or 18 August.” On the same day, Marshall endorsed the memo with the comment, “It is not to be released over Japan without express authority from the President.”[87] Truman had secretly requested this on August 10. This modified the previous order that the target cities were to be attacked with atomic bombs “as made ready”.[225]

There was already discussion in the War Department about conserving the bombs then in production for Operation Downfall. “The problem now [August 13] is whether or not, assuming the Japanese do not capitulate, to continue dropping them every time one is made and shipped out there or whether to hold them … and then pour them all on in a reasonably short time. Not all in one day, but over a short period. And that also takes into consideration the target that we are after. In other words, should we not concentrate on targets that will be of the greatest assistance to an invasion rather than industry, morale, psychology, and the like? Nearer the tactical use rather than other use.”[87]

Two more Fat Man assemblies were readied, and scheduled to leave Kirtland Field for Tinian on August 11 and 14,[226] and Tibbets was ordered by LeMay to return to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to collect them.[227] At Los Alamos, technicians worked 24 hours straight to cast another plutonium core.[228] Although cast, it still needed to be pressed and coated, which would take until August 16.[229] Therefore, it could have been ready for use on August 19. Unable to reach Marshall, Groves ordered on his own authority on August 13 that the core should not be shipped.[225]

Surrender of Japan and subsequent occupation

Until August 9, Japan’s war council still insisted on its four conditions for surrender. On that day Hirohito ordered Kōichi Kido to “quickly control the situation … because the Soviet Union has declared war against us.” He then held an Imperial conference during which he authorized minister Shigenori Tōgō to notify the Allies that Japan would accept their terms on one condition, that the declaration “does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign ruler.”[230]

On August 12, the Emperor informed the imperial family of his decision to surrender. One of his uncles, Prince Asaka, then asked whether the war would be continued if the kokutai could not be preserved. Hirohito simply replied, “Of course.”[231] As the Allied terms seemed to leave intact the principle of the preservation of the Throne, Hirohito recorded on August 14 his capitulation announcement which was broadcast to the Japanese nation the next day despite a short rebellion by militarists opposed to the surrender.[232]

In his declaration, Hirohito referred to the atomic bombings:

Moreover, the enemy now possesses a new and terrible weapon with the power to destroy many innocent lives and do incalculable damage. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.

Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects, or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.[233]

In his “Rescript to the Soldiers and Sailors” delivered on August 17, he stressed the impact of the Soviet invasion on his decision to surrender, omitting any mention of the bombs.[234] Hirohito met with General MacArthur on September 27, saying to him that “[t]he peace party did not prevail until the bombing of Hiroshima created a situation which could be dramatized”. Furthermore, the “Rescript to the Soldiers and Sailors” speech he told MacArthur about was just personal, not political, and never stated that the Soviet intervention in Manchuria was the main reason for surrender. In fact, a day after the bombing of Nagasaki and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria, Hirohito ordered his advisers, primarily Chief Cabinet Secretary Hisatsune Sakomizu, Kawada Mizuho, and Masahiro Yasuoka, to write up a surrender speech. In Hirohito’s speech, days before announcing it on radio on August 15, he gave three major reasons for surrender: Tokyo’s defenses would not be complete before the American invasion of Japan, Ise Shrine would be lost to the Americans, and atomic weapons deployed by the Americans would lead to the death of the entire Japanese race. Despite the Soviet intervention, Hirohito did not mention the Soviets as the main factor for surrender.[235]

Depiction, public response, and censorship

Life among the rubble in Hiroshima in March and April 1946. Film footage taken by Lieutenant Daniel A. McGovern (director) and Harry Mimura (cameraman) for a United States Strategic Bombing Survey project.

During the war “annihilationist and exterminationalist rhetoric” was tolerated at all levels of U.S. society; according to the British embassy in Washington the Americans regarded the Japanese as “a nameless mass of vermin”.[236] Caricatures depicting Japanese as less than human, e.g. monkeys, were common.[236] A 1944 opinion poll that asked what should be done with Japan found that 13% of the U.S. public were in favor of “killing off” all Japanese men, women, and children.[237][238]

After the Hiroshima bomb detonated successfully, Robert Oppenheimer addressed an assembly at Los Alamos “clasping his hands together like a prize-winning boxer”.[239] The bombing amazed Otto Hahn and other German atomic scientists the British held at Farm Hall in Operation Epsilon. Hahn stated that he had not believed an atomic weapon “would be possible for another twenty years”; Werner Heisenberg did not believe the news at first. Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker said “I think it’s dreadful of the Americans to have done it. I think it is madness on their part”, but Heisenberg replied, “One could equally well say ‘That’s the quickest way of ending the war'”. Hahn was grateful that the German project had not succeeded in developing “such an inhumane weapon”; Karl Wirtz observed that even if it had, “we would have obliterated London but would still not have conquered the world, and then they would have dropped them on us”.[240]

Hahn told the others, “Once I wanted to suggest that all uranium should be sunk to the bottom of the ocean”.[240] The Vatican agreed; L’Osservatore Romano expressed regret that the bomb’s inventors did not destroy the weapon for the benefit of humanity.[241] Rev. Cuthbert Thicknesse, the Dean of St Albans, prohibited using St Albans Abbey for a thanksgiving service for the war’s end, calling the use of atomic weapons “an act of wholesale, indiscriminate massacre”.[242] Nonetheless, news of the atomic bombing was greeted enthusiastically in the U.S.; a poll in Fortune magazine in late 1945 showed a significant minority of Americans (22.7%) wishing that more atomic bombs could have been dropped on Japan.[243][244] The initial positive response was supported by the imagery presented to the public (mainly the powerful images of the mushroom cloud) and the censorship of photographs that showed corpses and maimed survivors.[243] Such “censorship” was however the status-quo at the time, with no major news outlets depicting corpses or maimed survivors as a result from other events, US or otherwise.[245]

On August 10, 1945 the day after the Nagasaki bombing, Yōsuke Yamahata, correspondent Higashi and artist Yamada arrived in the city with orders to record the destruction for maximum propaganda purposes, Yamahata took scores of photographs and on August 21 they appeared in Mainichi Shimbun, a popular Japanese newspaper.[246]

Wilfred Burchett was the first western journalist to visit Hiroshima after the atom bomb was dropped, arriving alone by train from Tokyo on September 2, the day of the formal surrender aboard the USS Missouri. His Morse code dispatch was printed by the Daily Express newspaper in London on September 5, 1945, entitled “The Atomic Plague”, the first public report to mention the effects of radiation and nuclear fallout.[247] Burchett’s reporting was unpopular with the U.S. military. The U.S. censors suppressed a supporting story submitted by George Weller of the Chicago Daily News, and accused Burchett of being under the sway of Japanese propaganda. Laurence dismissed the reports on radiation sickness as Japanese efforts to undermine American morale, ignoring his own account of Hiroshima’s radiation sickness published one week earlier.[248]

The Hiroshima ruins in March and April 1946, by Daniel A. McGovern and Harry Mimura

A member of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, Lieutenant Daniel McGovern, used a film crew to document the results in early 1946.[249] The film crew’s work resulted in a three-hour documentary entitled The Effects of the Atomic Bombs Against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The documentary included images from hospitals showing the human effects of the bomb; it showed burned out buildings and cars, and rows of skulls and bones on the ground. It was classified “secret” for the next 22 years.[250] During this time in America, it was a common practice for editors to keep graphic images of death out of films, magazines, and newspapers.[245] The total of 90,000 ft (27,000 m) of film shot by McGovern’s cameramen had not been fully aired as of 2009. According to Greg Mitchell, with the 2004 documentary film Original Child Bomb, a small part of that footage managed to reach part of the American public “in the unflinching and powerful form its creators intended”.[249]

Motion picture company Nippon Eigasha started sending cameramen to Nagasaki and Hiroshima in September 1945. On October 24, 1945, a U.S. military policeman stopped a Nippon Eigasha cameraman from continuing to film in Nagasaki. All Nippon Eigasha’s reels were then confiscated by the American authorities. These reels were in turn requested by the Japanese government, declassified, and saved from oblivion. Some black-and-white motion pictures were released and shown for the first time to Japanese and American audiences in the years from 1968 to 1970.[249] The public release of film footage of the city post attack, and some research about the human effects of the attack, was restricted during the occupation of Japan, and much of this information was censored until the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951, restoring control to the Japanese.[251]

Only the most politically charged and detailed weapons effects information was censored during this period. The Hiroshima-based magazine, Chugoku Bunka for example, in its first issue published March 10, 1946 devotes itself to detailing the damage from the bombing.[252] Similarly, there was no censorship of the factually written witness accounts, the book Hiroshima written by Pulitzer Prize winner John Hersey, which was originally published in article form in the popular magazine The New Yorker,[253] on August 31, 1946, is reported to have reached Tokyo in English by January 1947, and the translated version was released in Japan in 1949.[254][255][256] The book narrates the stories of the lives of six bomb survivors from immediately prior, to months after, the dropping of the Little Boy bomb.[253]

Beginning in 1974 a compilation of drawings and artwork made by the survivors of the bombings began to be compiled, with completion in 1977 and under both book and exhibition format, it was titled The Unforgettable Fire.[257]

Post-attack casualties